Luke 20:27-38

Jesus had finally arrived in Jerusalem. Luke tells us in chapter 20 that Jesus was teaching in the temple every day. A sizeable crowd gathered around him to listen as he taught about the kingdom of God, but the scribes and temple authorities were continually trying to trip him up. “So they watched him,” writes Luke, “and sent spies who pretended to be honest, in order to trap him by what he said and then to hand him over to the jurisdiction and authority of the governor.” (Luke 20:20)

With that kind of framing from Luke, it’s natural to assume that the Sadducees in today’s gospel text have come to Jesus with a “gotcha” question. “Teacher,” they ask, “Moses wrote for us that if a man’s brother dies leaving a wife but no children, the man shall marry the widow and raise up children for his brother. Now there were seven brothers; the first married a woman and died childless; then the second and the third married her, and so in the same way all seven died childless. Finally the woman also died. In the resurrection, therefore, whose wife will the woman be? For the seven had married her.”

In order to really understand what’s going on in this little dialogue between Jesus and the Sadducees, it’s probably helpful for us to understand more about who the Sadducees were and what levirate marriage is.

The Sadducees were a conservative Jewish sect whom the Romans had placed in charge of operating the Temple. They were well educated, well connected, often wealthy and they focused on maintaining the well-organized and efficient operation of the Temple as a way to safeguard their elite status and positions of power. They believed in free will, that each individual has complete control over their own destiny and choices, and they rejected any notion that fate or divine intervention played any kind of role in our lives.

In religious matters the Sadducees accepted only the written Torah as authoritative and rejected the oral traditions and rabbinic interpretations that the Pharisees considered authoritative. They also entirely rejected the supernatural. They did not believe in angels, demons, resurrection or any kind of afterlife with rewards and punishments because none of those things were mentioned in Torah. They believed that when the body died the soul died with it.

Levirate marriage—the Hebrew word for it is Yibbum—is pretty much exactly what the Sadducees describe in their question to Jesus. Deuteronomy 25 spells it out this way: “When brothers reside together and one of them dies and has no son, the wife of the deceased shall not be married outside the family to a stranger. Her husband’s brother shall go in to her, taking her in marriage and performing the duty of a husband’s brother to her,and the firstborn whom she bears shall succeed to the name of the deceased brother, so that his name may not be blotted out of Israel.”

While the whole thing sounds pretty misogynistic to our ears—the woman is still treated more or less as property after all—this practice actually had some very real benefits for the widow in their frankly patriarchal culture. Levirate marriage ensured that the widow remained financially supported and that she remained connected to her husband’s family. It protected children and safeguarded their family identity and inheritance rights. It provided an heir for the deceased man which allowed his name and legacy to be carried on, and it promoted cohesion and continuity within the clan by keeping wealth and property in the family. And to be fair, either the widow or the brother-in-law could opt out of the arrangement with a ritual called Chalitzah which is also described in Deuteronomy 25, although there was a certain amount of shame attached to doing that.

As I said earlier, the question that the Sadducees ask Jesus sounds like a “gotcha” question, especially since Luke has flat-out stated that the Temple authorities “were trying to trap him.” But Diana Butler Bass has suggested that there might be another way to hear their question.

What if these Sadducees are being sincere in their question? What if these men who did not believe in life after death were asking Jesus about the resurrection because they were afraid that maybe, just maybe, there really is more to come after we die? What if they’re afraid because their whole tradition has taught them not to believe that, but now they have questions and their tradition has no answers?

That’s a precarious place to be when you’re living through a time of turmoil and uncertainty, when the Empire might suddenly decide there has been one too many subversive acts and it’s time to break out the swords and spears. Theirs was a precarious and disquieting belief, a belief without hope or comfort, in a world or culture where at any given moment and for the flimsiest of reasons, death could be waiting just the other side of the door.

The way you hear the Sadducees’ question can affect the way you hear Jesus’ answer. If you hear him responding to just another “gotcha” question, he might actually sound a bit snarky in his response. But if he is responding to a sincere question that rises out of their fear of death, then he sounds like a good pastor addressing their fears with comfort and understanding as he explains a theological mystery. “Those who belong to this age marry and are given in marriage, but those who are considered worthy of a place in that age and in the resurrection from the dead neither marry nor are given in marriage. They can’t die anymore. They are like the angels. They are children of God!”

And then, to bring it home, he gives them an argument from the Torah, the one part of the scriptures they trust. He gives them an example from Exodus: “The fact that the dead are raised Moses himself showed in the story about the bush. He speaks of the Lord as the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. He speaks of God not as God of the dead but of the living. For to God all of them are alive.”

The big problem for the Sadducees is that they had decided in advance what they would and would not hear, what they would and would not read. They had eternal questions but their tunnel vision would not even let them read their own favorite sources in a more expansive and comforting way.

Because they would only read Torah, the Pentateuch—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy—they couldn’t hear the jubilant voice of Isaiah saying, “Your dead shall live; their corpses shall rise. Those who dwell in the dust will awake and shout for joy! For your dew is a radiant dew, and the earth will give birth to those long dead.”[1] They were deaf to the voice of Ezekiel saying, “Thus says the Lord God: I am going to open your graves and bring you up from your graves, O my people!”[2] They never heard Daniel saying “Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to shame and everlasting contempt.”[3]

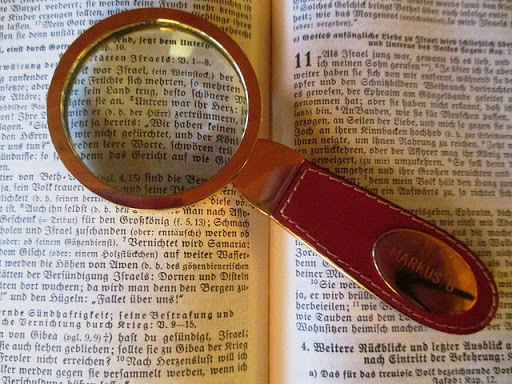

The Sadducees didn’t have a problem with their Bible. They had a problem with the way they were reading their Bible. They were missing the best parts! They were missing the promises and the good news! And they were missing those things because they thought they already knew what it said. They thought they already knew which parts were most important.

That can happen to any of us. Our assumptions can cause us to miss things that are life-changing.

I get Richard Rohr’s Daily Meditations from the Center for Action and Contemplation in my email every morning. I usually read it, but sometimes, if it looks like something I’ve seen before, I just discard it. When I opened Friday’s meditation, I noticed right away that it was about the beatitudes. Well, I’ve read the Beatitudes in English and Greek and preached on them for 30 years. I’m pretty familiar with the Beatitudes. I was about to drag the meditation to the electronic bin when my eye caught the word Aramaic.

This post, this particular meditation, was written by Elias Chacour, a Palestinian Arab-Israeli who is the former archbishop of the Melkite Greek Catholic church in Palestine. Bishop Chacour had things to say about the Beatitudes that I had never read or heard before, and taking time to read what he said has given me a whole new way to understand them.

“Knowing Aramaic, the language of Jesus,” he wrote, “has greatly enriched my understanding of Jesus’ teaching. Because the Bible as we know it is a translation of a translation, we sometimes get a wrong impression. For example, we are accustomed to hearing the Beatitudes expressed passively:

“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice, for they shall be satisfied.

“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.

“Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.

“’Blessed’ is the translation of the word makarioi, used in the Greek New Testament. However, when I look further back to Jesus’ Aramaic, I find that the original word was ashray, from the verb yashar. Ashray does not have this passive quality to it at all. Instead, it means “to set yourself on the right way for the right goal; to turn around, repent; to become straight or righteous.”

“When I understand Jesus’ words in Aramaic, I translate like this:

Get up, go ahead, do something, move, you who are hungry and thirsty for justice, for you shall be satisfied.

Get up, go ahead, do something, move, you peacemakers, for you shall be called children of God.

“To me this reflects Jesus’ words and teachings much more accurately. I can hear him saying, “Get your hands dirty to build a human society for human beings; otherwise, others will torture and murder the poor, the voiceless, and the powerless.” “Christianity is not passive but active, energetic, alive, going beyond despair….

“Get up, go ahead, do something, move,” Jesus said to his disciples.”[4]

When we take away our preconceived notions of what we think the scriptures are supposed to say, when we let new voices inform our reading, it can be life changing.

Life is eternal. Love is immortal. So ashray! Get up, go ahead, do something, move! In Jesus’ name.

[1] Isaiah 26:19

[2] Ezekiel 37:12-14

[3] Daniel 12:2

[4] Daily Meditations, Center for Action and Contemplation; Friday, November 7, 2025