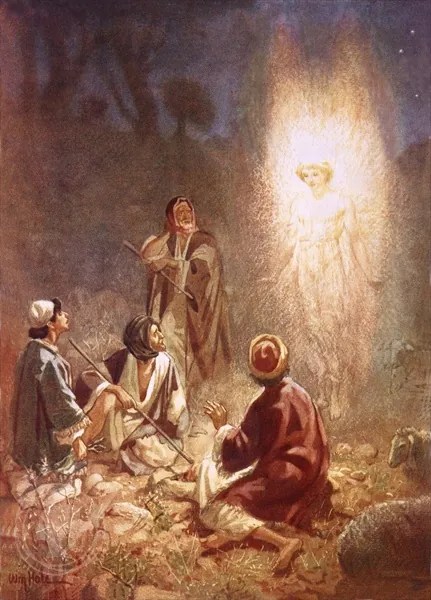

Then an angel of the Lord stood before them, and the glory of the Lord shone around them, and they were terrified. –Luke 2:9 (NRSV)

It’s funny how you can look at something a hundred times or more and then one day someone will point out something you hadn’t noticed and the whole thing looks different to you. That happened to me a few years ago when a colleague pointed out one simple word in Luke’s Christmas story that had always just flown right by me.

Stood. That was the word. Stood.

The angel stood before them. On the ground.

In all the years of reading or hearing this Christmas story I had always imagined this angel and the multitude of the heavenly host hovering in the air. I think the Christmas carols taught us to picture it that way. Angels we have heard on high. It came upon a midnight clear, that glorious song of old, from angels bending near the earth.

But that’s not what it says in the Gospel of Luke. The angel stood before them.

If you were a shepherd in a field on a dark night, it would be pretty unsettling to have an angel appear in the air above you making announcements, but at least if the angel is in the air there’s some distance between you—a separation between your environment and the angel’s. But if the angel suddenly appears standing in front of you, standing on the same ground you’re standing on, shining with the glory of the heavens… well I think my knees would turn to rubber. And then imagine what it feels like when the whole multitude of the heavenly host is suddenly surrounding you and singing Glory to God.

Angels in the air feels slightly safer than angels on the ground. Slightly. If the angels are above, that means that they came from above. It means that heaven is “up there” somewhere. It doesn’t mess with the way we understand the spiritual cosmos. But if the angels appear standing in front of us or behind us or around us, what does that say about heaven? Could it be that heaven, the dwelling place of God and the angels, is not just “up there” but also here, with us? Around us? Could it mean that the angels of God are standing near us all the time and they simply choose not to show themselves? Or that we’re just blind to their presence? Could it mean that this ground we walk on and build on and live on is also part of the dwelling place of God—so holy ground?

The angels didn’t bend near the earth. They stood on it.

We have this tendency, we humans, to want to separate the material from the spiritual, the divine from the physical. We are such binary, black and white thinkers in a universe that’s full of colors and shades of gray. We want here to be here and there to be there. We want to put borders even on the oceans and talk about territorial waters! We want to draw a clear and well defended line between our country and the country next door. So it’s not surprising that we’ve assumed that there is a border between heaven and earth.

We seem to be most comfortable when there’s a little distance between us and angels, a little distance between us and God. That seems to be the way most people talk about it, anyway. “Put in a good word with the man upstairs,” they say. And then there’s that song: “God is watching from a distance.”

But that’s not what Christianity says. That’s not what Christmas says. The Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father’s only son, full of grace and truth. In him the fullness of God was pleased to dwell. Not from a distance, but right in front of us. With us. As one of us.

We have trouble seeing the presence of God, seeing Christ in creation. We have trouble seeing Christ in each other. We even have trouble understanding Christ in Jesus. How can Jesus be both divine and human? We struggle to wrap our minds around that idea, so we have a tendency to make him either all human or all divine. We picture that baby in the manger with a halo, and it doesn’t cross our minds that he might need to breastfeed and be burped and he might need his diapers changed.

Christmas, the mystery of the incarnation, tells us that God is not a bearded old man watching us from the clouds, a deity who is willing to give us what we ask if we are really good or strike us down with a thunderbolt if we’re bad. That’s not God. That’s Santa Claus. Or Zeus.

God, the Author of Life, the One in whom we live and move and have our being is Love with a capital L. Love Personified. And Love is all about relationship. Christmas is when God, the Love that created the universe, showed up as one of us in order to show us in person just how much we are loved and in order to teach us to how to love each other more freely and completely.

“We need to see the mystery of incarnation in one ordinary concrete moment,” wrote Richard Rohr, “and struggle with, fight, resist, and fall in love with it there. What is true in one particular place finally universalizes and ends up being true everywhere.” In other words, God is present everywhere, in, with, and under everything. Including you. And me. And all those people we’re inclined not to like. But to really grasp this idea, we need to first see God fully present in one particular person. We need to see God in this particular baby. This human baby

That, in the end, is what Christmas, the incarnation, is trying to tell us. Christmas is God’s way of teaching us that there never really was any distance between heaven and earth, between the divine and the human, between the spiritual and the material. Christmas is God proving once again that Christ is in, with, and under all the things—all things—including all the things we think we oversee and all the things we overlook. Christmas is angels standing on the earth singing to shepherds and surrounding them with the glory of the Lord to remind them that they, too, are spiritual beings immersed in a human experience.

Christmas is God’s love made visible. Pope Francis said, “What is God’s love? It is not something vague, some generic feeling. God’s love has a name and a face: Jesus Christ, Jesus.” I would add that, if you open your heart and your mind to it, God’s love can have your face, too.

Love is vulnerable—and what’s more vulnerable than a baby? God comes to us as a baby because it’s easy to love a baby. It’s easy to be vulnerable with a vulnerable infant.

Christmas is homey and concrete and vulnerable. It enters the world surrounded by the earthy aromas of animals. It needs to be fed at a mother’s breast. It needs its diapers changed. It cries when it’s hungry and shivers when it’s cold. It spits up a little bit on your shoulder. It looks out at the world with brand new eyes and tries to see and understand what it sees. Most of all, it reaches out to be picked up and held close to your heart. Christmas wants to be loved and to give love.

Christmas is our down-to-earth God made manifest. Yes, gloria in excelsis deo, glory to God in the highest, but glory, too, to God on earth where the angels stand to sing to shepherds, because the Spirit of God is in them, too, and God loves them like crazy. Just like God loves you.

My prayer for you this Christmas is that you would enter deeply into the concrete, down-to-earth, human and divine mystery of incarnation. May your eyes and ears be opened to the angels who stand upon the earth and minister to all God’s children. May you come to see Christ incarnate, permeating all creation. May you come to see that you are always and everywhere standing on holy ground. May you dispense with artificial borders in your heart, in your mind, and in this lovely world. And may you come to see yourself and all the others who share this world with you as spiritual beings immersed in a human experience. Most of all, though, may you know that you are loved.

May Christ be born anew in your heart this day and every day. In Jesus’ name.