Clergy persons often refer to this Sunday as Shepherd Sunday or Good Shepherd Sunday because of the lectionary readings assigned for today, but I’m going to depart from the lectionary because it’s also Mother’s Day.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my mom. She was an amazing woman—a social worker and, until cancer cut her life short, a law student. She was smart, generous and loving. She had a great sense of humor and a deep and vibrant faith. She’s probably the reason I became a pastor. And I’ve missed her every day of the last 36 years

My mom told me once that I’d never amount to much because I procrastinate too much. I said, “Oh yeah? Well just you wait.”

I’ll never forget one Mother’s Day—we had a big family meal at Mom and Dad’s house but right after dinner Mom kind of disappeared. I found her in the kitchen getting ready to wash a sink full of dirty dishes. I said, “Mom, it’s Mother’s Day! Go sit down and relax. You can do the dishes tomorrow.”

Mothers Day was first proposed by Julia Ward Howe and other feminist activists just after the Civil War. Julia Ward Howe, by the way, wrote The Battle Hymn of the Republic. These women originally envisioned Mothers Day as a day for mothers around the world to come together to promote international peace, and also to honor mothers who had lost sons and husbands to the carnage of the war. Unfortunately, aside from a few stirring proclamations, their efforts didn’t produce much.

A few decades later, though, Anna Maria Jarvis almost single handedly managed to make Mothers Day a national holiday. Inspired by her mother’s wish to see a national day honoring mothers, Anna Jarvis began promoting the idea throughout the country. By 1911 Mothers Day was being observed in every state, and in 1914, President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation officially designating the second Sunday in May as Mother’s Day.

And here’s an odd but important note: originally there was no apostrophe in Mother’s Day. Julia Howe and Anna Jarvis both envisioned it as a day to honor all mothers. Plural. But the greeting card industry, the florists, and the candy makers quickly idealized it and individualized it and began promoting it as a day for you to honor your mother. In their advertising, Mothers Day (plural/all mothers) quickly became Mother’s Day with an apostrophe, as in your particular mother’s day (singular/possessive). Needless to say, the idea of it being a day to promote international peace pretty much vanished with the arrival of that apostrophe.

Ann Jarvis, who had worked so hard to make Mother’s Day a national observance, ended up hating it. The holiday became so commercialized, that in 1943 she tried to organize a petition to rescind Mother’s Day, but her efforts went nowhere. Frustrated, and literally at her wits’ end, Anna Jarvis died in 1948 in a sanitarium. Ironically, her medical bills were paid by a consortium of people in the floral and greeting card industries.

As joyful and sentimental as Mother’s Day is for some, others find it almost unbearably painful. Anne Lamott’s Mother’s Day column which she re-posts every year begins this way: “This is for those of you who may feel a kind of sheet metal loneliness on Sunday, who had an awful mother, or a mother who recently died, or wanted to be a mother but didn’t get to have kids, or had kids who ended up breaking your hearts…” Lamott goes on to acknowledge many of the ways that this Greeting Card holiday can be painful for many women…and also for many children.

Most pastors I know are ambivalent at best when it comes to Mother’s Day. It’s something of a minefield for us. We don’t dare let it go unmentioned, but at the same time we are very aware of those women in our congregations who for one reason or another will be feeling that “sheet metal loneliness” that Anne Lamott talks about.

On the plus side, though, Mother’s Day does give us an opportunity to highlight issues that women face in a world and culture that still operates with far too much patriarchal dominance and oppression, often in ways that men don’t even see.

One of the most persistent and troubling issues that women face is the gender pay gap, the disparity in earnings between women and men that gets amplified when those women and men are mothers and fathers. Often referred to as the “motherhood penalty,” this phenomenon sees mothers earning significantly less than fathers, even when they possess similar qualifications and experience. Overall nationally, mothers were paid 61.8 cents for every dollar paid to fathers. In 2023, mothers who worked full-time year-round were paid 74.3 cents per dollar paid to fathers. That means that mothers earned $19,000 lessfor a year of full-time work, an amount that’s roughly equal to the cost of infant care.[1]

Mothers of color face an even larger earning gap when compared to White fathers. Nationally, in 2023, Black mothers earned 48.8 cents per dollar paid to White fathers, Native American mothers earned 48.2 cents, and Latina mothers earned 42.7 cents per dollar paid to White fathers.

In contrast to the “motherhood penalty,” fathers often experience a “fatherhood bonus,” where their earnings may actually increase following the birth of a child. Employers tend to perceive fathers as more stable and committed to their jobs, leading to higher wages and better career prospects. This bias not only perpetuates economic inequality but also reinforces traditional gender roles within the family and the workplace.

This economic inequality is so very contrary to the values of the kingdom of God, or as Diana Butler Bass calls it, the Commonwealth of God’s justice and mercy. In his letter to the Galatians, St. Paul wrote, “In Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith. . .There is no longer Jew or Greek; there is no longer slave or free; there is no longer male and female, for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.” In his book The Forgotten Creed: Christianity’s Original Struggle Against Bigotry, Slavery, and Sexism, Stephen J. Patterson points out that this egalitarian statement did not originate with Paul. Rather, Paul is quoting a baptismal creed that was already in use by early Christian communities, a creed which Patterson describes as one of “the earliest attempts to capture in words the meaning of the Jesus movement.”

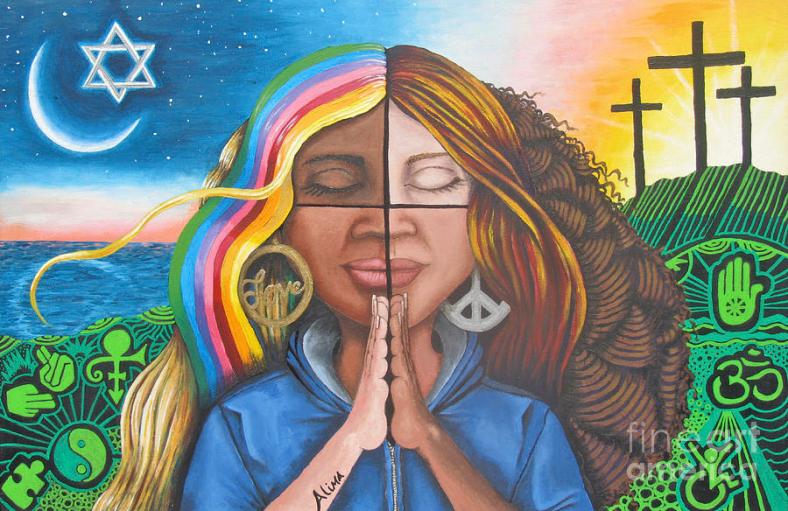

These early Christians understood that race, class and gender are typically used to divide the human race into us and them. When these earliest Christians listened to the voice of their good shepherd, they believed that Jesus was calling them to live in radical equality. In their baptismal creed, these early followers of Jesus claimed that there is no us versus them. We are all one. We are all children of God. We are all equal.

Unfortunately, the radical egalitarianism of these earliest Jesus communities didn’t last long. Their way of life made these communities stand out too sharply in contrast to the patriarchal and hierarchical norms of the Roman culture that surrounded them. Living out this radical equality made the followers of Jesus more visible and vulnerable when Roman authorities began to persecute them.

And now here we are, two thousand years later and, despite some progress, people are still, by and large, expected to fulfill traditional roles, and the culture punishes those who don’t or won’t. One of the problems with Mother’s Day is that it reinforces a cultural expectation that puts the weight of parenting primarily on Mom. That’s unfair to Mom and limits a child’s experience because even Super Mom can’t really do it alone. As the old African proverb reminds us, it takes a village to raise a child.

“My main gripe with Mother’s Day,” said Anne Lamott, “is that it feels incomplete and imprecise. The main thing that ever helped mothers was other people mothering [their children], including aunties and brothers; a chain of mothering that keeps the whole shebang afloat. I am the woman I grew to be partly in spite of my mother, who unconsciously raised me to self-destruct; and partly because of the extraordinary love of her best friends, my own best friends’ mothers, and from surrogates, many of whom were not women at all but gay men. I have loved them my entire life, including my mom, even after their passing.”

Raising children is a community affair. It should be done with an eye on what’s best for the community. We lose sight of that too often. We think good parenting means raising kids who will share our cherished internal family values. That’s only natural, but the child really needs to be prepared for the time when they will leave home to enter the world on their own. They need to be prepared not just to make a valuable contribution to the community, but to be a positive contribution to the community.

Parents need to remember that their children are not just a gift that God gives to them, but a gift that they, in turn, give to the world. We need to send our children into the world equipped with empathy, wisdom, patience and understanding. As Barbara Kingsolver said, “We want our children to grow up in a culture of kindness and generosity.” They need to have a clear understanding of and feeling for the intrinsic value of other people. Developing those attributes requires more influence than any one parent can provide. And I have to say, I think a lot of the problems we’re facing today as a nation are a direct result of too many people in positions of authority who were raised without that extended community and without those values—especially an understanding of the intrinsic value of other people.

Jesus told a story in chapter 20 of the Gospel of Matthew about a man who went to the marketplace one morning to hire some workers, and before sending them out to work in his vineyard, he made a verbal contract with them to pay them the basic daily wage of one denarius. A few hours later, he went to the marketplace again and hired some more workers and said, “I will pay you whatever is right.” He went to the marketplace three more times during the day to hire more workers, the last time just an hour before sunset, and each time he told those workers that he would pay them “whatever is right.” At the end of the day when all the workers lined up to receive their pay, he paid the workers who had only been in the field for an hour one denarius, the whole day’s wage. Naturally, the workers who had been working since sunrise figured they were in for one heck of a bonus, but when it was their turn to be paid, the man also paid them one denarius, the standard daily wage. They were upset about this and groused about it. “These latecomers only worked an hour and you have made them equal to us even though we were out here in the heat all day!” The landowner responded, “Friend, I am doing you no wrong; didn’t you agree with me for the usual daily wage? I chose to give the latecomers the same as you. Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?”

This parable makes a lot of people squirm, mostly because we tend to feel slighted on behalf of those workers who were out in the hot sun all day. On the flip side, we tend not to feel any joy on behalf of the one-hour workers who got what amounts to an astonishing bonus. I think we feel all this because we lose sight of what this parable is all about and our focus is in the wrong place.

This is not just a story about wages—how much should the fieldworker get paid per hour—or how much should a mother be paid—this is a story about what’s best for the community. Jesus starts the story by saying “The kingdom of heaven is like…” The context is bigger than the owner of the vineyard or the workers.

The landowner understands that his wealth, his resources are not just for his own personal benefit or his family’s, but are meant to be used to make the whole community healthier and stronger. I suppose you could say he’s “mothering” the community. He understands that he is not just paying workers to harvest his grapes on his property, rather, he is providing a means of support for the whole community. He understands that by paying the one-hour worker the full day’s wage, he is creating one less beggar in the marketplace while preserving that person’s dignity and helping to feed that worker’s family for days. He understands that by paying all the workers the same wage he is sending the message that they are all equally vested in the good of the community.

In this short story by Jesus, the workers who complained saw what the land owner was doing and they didn’t like it. They said, “you have made them equal to us.” In our country today there are still people who don’t like it when you propose making the richest people carry a larger share of the tax burden that supports our government and systems that benefit all of us, or if you propose something like single-payer universal healthcare, something they may not use because they can afford good private medical care but something that would, nonetheless, be beneficial for everyone else. Something that would strengthen the community.

“You have made them equal to us.” What is it in us that rebels at true equality? Why do we have this desire, this expectation that some should be more equal than others? Why do some people work so hard to limit or prevent diversity, equity and inclusion and to preserve stratification of society even when it results in less qualified people doing critical jobs? Why is it so hard for some to understand that when we try to live by the ethics of equality and inclusion that Jesus modeled for us, we’re not trying to displace them, we’re just trying to build solidarity within diversity? And why did the church lose sight of its beautiful and powerful first creed?

In Christ there is no longer Jew or Gentile, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female. We are all God’s children.

And that brings us back around to the original intent for Mothers Day. It was intended to be something to strengthen the community and bring peace to the world. Just like our Christian faith.

In Jesus’ name.

[1] Institute for Women’s Policy Research, Fact Sheet, May 2025