James 3:1-12; Mark 8:27-38

It has been a stressful week in Springfield, Ohio. A middle school was closed on Friday and two elementary schools were evacuated because of bomb threats. Yesterday, three medical facilities in Springfield were targeted with more bomb threats. The police have beefed up their staffing because racist threats of violence against Springfield’s Haitian immigrant community have been circulating and there is concern that these threats could escalate into actual violence.[1]

Things were already a bit uneasy in Springfield, a mostly blue-collar city of about 60,000 residents. The city’s manufacturing economy was hit hard by the Covid shutdown and economic renewal, while steady, has been moving more slowly than they had hoped. Over the past few years about 15,000 Haitian immigrants have been drawn to the city by new factory jobs and relatively affordable housing, but some of the longtime residents, mostly white, have been antagonistic to the newcomers, accusing them of driving up housing costs and straining city services.

All of this came to a head last week when a neo-Nazi group fabricated a story about the Haitian immigrants kidnapping and eating their neighbors’ household pets. This racially inflammatory story moved from the social media platform Telegram to X where it was picked up by Vice-Presidential candidate J.D. Vance who repeated it as part of a verbal jab Vice President Harris even though the story had already been debunked by the mayor of Springfield and police officials. When former President Trump repeated the story during Tuesday night’s presidential debate, the lie about immigrants eating cats and dogs immediately became the source of countless jokes and memes, but the people of Springfield aren’t laughing, especially not the Haitian community. Some of them are afraid to leave their homes.

“How great a forest is set ablaze by such a small fire! And the tongue is a fire,” we read in the chapter three of James. “The tongue is placed among our members as a world of iniquity; it stains the whole body, sets on fire the cycle of life, and is itself set on fire by hell —a restless evil, full of deadly poison. With it we bless the Lord and Father, and with it we curse people, made in the likeness of God.”

Words have power.

This week we observed a horrible anniversary, the commemoration of an event that upended our world and set enormous changes in motion. Coming, as it did, on the day after an important presidential election debate, this anniversary was overlooked by many, but in many ways the explosive shock of that day is still reverberating throughout our nation and the world.

It was twenty-three years ago, September 11, 2001, when terrorists violently assaulted our religious, social, economic, and political structures by crashing three planes into the World Trade Towers and the Pentagon. Analysts think that the fourth plane, which was heroically brought down by its passengers, was intended to crash into the US Capitol building or the White House.

The heinous action of the terrorists was born in words. It was a statement, a word of hatred, self-righteousness, religious piety and vitriol, but its inarticulate message was incinerated in the flames and destruction of its violence. How great a forest is set ablaze by a small fire.

Words have power.

In the aftermath of that violent act, a lawyer sat down at his computer and wrote a sentence, a 60 word run-on sentence that blurred the line between war and peace, a sentence that led us into the longest war this country has ever known. On September 18, 2001, that 60-word sentence was adopted by both houses of Congress and signed into law as the Authorization for Use of Military Force.

Words have power.

In the Gospel lesson from two weeks ago, some Pharisees and scribes gave Jesus a bad time because his disciples didn’t wash their hands before eating. So Jesus said to the crowd, “Listen and understand: it is not what goes into the mouth that defiles a person. It’s what comes out of the mouth that defiles. What comes out of the mouth gets its start in the heart. It’s from the heart that we vomit up evil arguments, murders, adulteries, fornications, thefts, lies, and racism. That’s what pollutes.”

Words have power.

In last week’s Gospel lesson, Jesus traveled to the region of Tyre and Sidon. The people of Israel had a low opinion of the people of Sidon and Tyre, an opinion rooted in a long history of animosity between the two regions. When a woman from the area asked Jesus to free her daughter from a demon, Jesus insulted her. “It’s not right to give the children’s food to the dogs,” he said. He called her a dog. You have to wonder why he would say such a thing.

Did Jesus, the same Jesus who was criticized for hanging out with tax collectors and “sinners,” the same Jesus who crossed all kinds of boundaries to embrace all kinds of outcasts, the same Jesus who touched lepers! did this Jesus trek all the way to the heart of Sidon just to insult this poor woman with a racial slur?

Yes. Yes he did. Jesus schlepped all the way to Sidon to create a teaching moment that his disciples and all his followers forever after would not forget. Words have power. Especially the ugly ones.

In that moment with that desperate woman, Jesus said aloud what his disciples were thinking. He wanted them to hear the ugliness of their attitudes out loud. He led them to the neighborhood of “those people,” the ones who they think are inferior, the ones who they think are cursed. The ones who, in their understanding, God doesn’t much care for.

I am not for one moment suggesting that the disciples in particular or Jews in general were xenophobic. I’m suggesting that almost all of us are to one degree or another. We humans have a bad tendency to “other” each other. And we do it with our words.

Words have power. Words have consequences.

It’s not what goes into the mouth that pollutes, it’s what comes out of the mouth. It’s from the heart that we vomit up lies, blasphemies, bigotries, othering and racism. That’s what pollutes us. That’s what poisons us generation after generation.

Our words have power.

At the beginning of the Gospel of Mark, Jesus begins his campaign to change the world with an announcement. He proclaims that the Reign of God is arriving. Everything that happens in Mark’s gospel pivots around that opening announcement: The reign of God, the dominion of God, the commonwealth of God’s justice and mercy, the kingdom of God—is arriving.

The announcement, itself, the very language of it, has power. Jesus doesn’t announce that the Kingdom of God has arrived, but that it is within reach. The message is that even though Jesus, the Christ has arrived to inaugurate the reign of God, it’s not a done deal. And maybe it never will be. The language Jesus uses tells us that the kingdom may always be a work in progress.

In chapter 8 of Mark, smack in the middle of the gospel, the disciples come to an inflection point, a crossroads. Mark wants us to understand that if we follow Jesus and try to live his Way, at some point their inflection point will become our crossroads, too. And it will all hang on a word. Because words have power.

Jesus asks his disciples, “Who do people say that I am?” It’s an easy question. What’s the buzz? What’s the word out there in the crowd? What do the polls say?

They told him that some people thought of him as John the Baptist. Others thought of him as Elijah. They all pretty much agreed that at the very least he was a prophet.

At this point, the question Jesus is asking is theoretical. The words are speculative. The question and the answers are all in the realm of rumor. It’s about what people are thinking. It’s a head question and the answers are all nothing more than opinion.

But words have power. When Jesus redirects the question and asks his disciples point blank, “Who do you say that I am, he puts them on the spot. Suddenly the question becomes visceral. And so do all possible answers. Words have power. And that power becomes action.

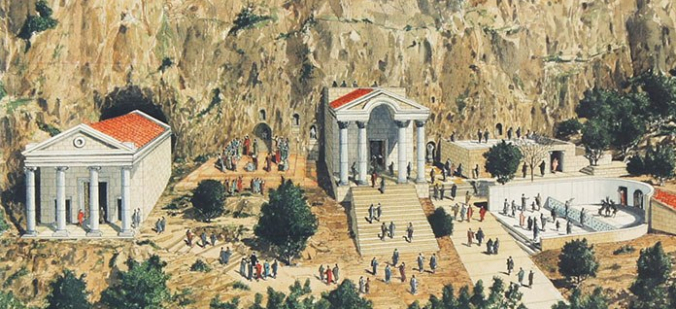

The geographic location where Jesus asks this question is speaking its own words of power. They are in Gentile territory just outside Caesarea Phillipi, a city famous as a center of pagan worship, most notably worship of the god Pan—a very sexy and earthy deity. They are at the edge of a city that was reconstructed by and named for the Tetrarch Phillip, the sycophant son of the ruthless Herod the Great. In an effort to curry favor with his Roman overlords, Phillip also dedicated the city to Caesar, the Roman Emperor, a dictator who claimed to be divine. On top of all that, Caesarea Phillipi was the place where the Roman legions took their R&R. And when those same Roman legions marched into Palestine to put down Jewish rebellion, they launched their campaigns from Caesarea Phillipi.

Here, in a place that confronted the disciples with pagan gods and stared them down with the brute force of its political and military might, here is where Jesus asked them—and asks us—his pointed question: “Who do you say that I am?” In the face of the allure of mythical nature religion and all the idols that seduce us, in the face of intimidating political power, in the face of the addictive efficiency of brute force, in the face of a world noisy with rumor and gossip and inuendo, Jesus asks “Who do you say that I am?”

Peter said, “You are the messiah. The Christ.” Is that your answer, too? What does that word mean to you? Messiah. Christ. What consequences come with that word, that identity?

Jesus, apparently, did not like the way Peter and the others interpreted that word. Messiah. He told them not to say it. He told them not to talk about him in those terms. He didn’t deny that he was the Messiah, but he knew that they were thinking of Messiah in terms of political power. Coercive clout. Military might. Maybe he was worried that they might be thinking of doing something rash and violent—the first century equivalent of flying planes into Rome’s symbolic towers.

So he told them to keep quiet.

Then he told them about the cross. He told them that if they really were his disciples there would be a cross for them, too.

Peter didn’t like what Jesus was saying. Peter was thinking of Messiah as a righteous general who would lead a holy army into a holy war, but Jesus was telling him he wasn’t willing to play that role, that pitting violence against violence was not the way to bring about a world of nonviolence. So Peter argued with Jesus right there in front of everybody.

How often do we argue with Jesus because he won’t play the role we want him to play? How often are we looking for a Messiah who will kick tail and take names and step in and fix everything? That seems to be what Christian Nationalism is all about, but if Jesus wasn’t willing to do it then, why does anyone think he would be willing to do it now?

In Mark’s gospel, acknowledging Jesus as Christ, living life as a follower of Jesus, means standing in opposition to both the religious and political systems that enrich and empower some while simultaneously creating a permanent underclass of the oppressed and disadvantaged. The first readers of Mark understood that Jesus was asking for a total commitment to his nonviolent revolution, his transformation and restructuring of the world to bring it into conformity with God’s vision.

Jesus is still asking that of us. But he wants us to understand that there are consequences for standing against the powers. He also, however, wants us to understand that there are consequences for not doing it, for continuing to play along with all the forces of business as usual.

“What good will it be if you play the game and get everything you want, the whole world even, but lose your soul? Your very self? What are you going to get in exchange for selling off your soul in little pieces? What’s the going rate for that internal eternal essence that makes you uniquely and creatively you? What’s the market price for the image of God in you? What good will it be at the end of the day if you’re surrounded by every comfort but you’ve lost everything that makes you really you, everything in you that shines with the likeness of God?

Be careful how you answer. Words have power.

[1] ABC News, September 14, 2024