Luke 2:22-49

Welcome to the Sunday of Colliding Traditions! Today, December 31, is the seventh day of Christmas—seven swans a-swimming—and also the first Sunday of Christmas. And in the secular calendar it’s New Year’s Eve.

People throughout the world have all kinds of interesting rituals and traditions for welcoming in the new year. Meri and I have a tradition of eating shrimp on New Year’s Eve. It seems to work for us, so I was glad to learn that a number of Asian cultures think eating shrimp on New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day brings good luck. Other cultures, however, think eating shrimp brings bad luck because shrimp swim backward—away from the good fortune that’s heading your way. The same goes for lobster.

In Ecuador people set fire to effigies at midnight on New Year’s Eve. These effigies are stuffed with paper containing brief descriptions of bad situations people want to escape or undesirable things or even photographs of things they would like to be rid of. And it’s important that the effigy be burned completely or the bad situations will return.

In the Philippines people try to use as many round things as possible as they celebrate the new year—round food, round clothing, round candies. The round things represent coins so this ritual is a way to encourage the New Year to bring them greater wealth.

In Denmark people save up old plates all year then hurl them against the front doors of their friends’ houses on New Year’s Eve in a ritual that is supposed to bring good fortune. I have no idea how or why that’s supposed to work.

In Spain people begin to pop grapes into their mouths as the clock begins to strike 12. The goal is to get 12 grapes into your mouth—one with each chime of the clock—to ensure good luck for every month of the new year.

Buddhists in Japan literally ring in the new year, not with 12 chimes of the clock, but by ringing a bell 108 times. They believe this ritual banishes all human sin. In Japan it is also considered good luck to be smiling or laughing as you enter the new year.

In Germany many people enjoy a traditional meal of Silvesterkarpfen (New Year’s Carp) on New Year’s Eve. It is considered good luck to keep a scale from the carp in your wallet throughout the year to bring wealth and good fortune. But be careful that the scale doesn’t slip out when you reach for your cash because removing the scale removes the good luck.

In Mexico, Bolivia, Brazil and other parts of Central and South America, the color of your underwear is very important on New Year’s Eve. Red or pink is for those who hope to find love in the new year. Yellow or gold ensures prosperity. Green is for hope and white is for peace. If you want to really ensure that this charm works, make sure your New Year’s skivvies are brand new.

Rituals and traditions shape us. Even the odd ones. Especially the odd ones. They tell us who we are and where we fit in the world. Joseph Campbell said that in our rituals we enact and participate in our myths, the central and formative stories that shape us as a people. When you participate in a ritual, he said, “your consciousness is being re-minded of the wisdom of your own life.”

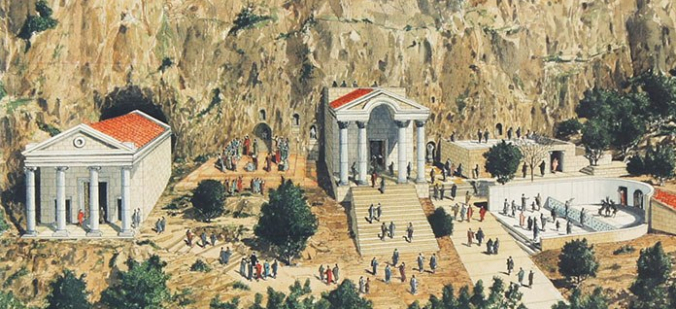

“When the time came for their purification according to the law of Moses, they brought him up to Jerusalem to present him to the Lord.” Forty days after his birth, Mary and Joseph brought Jesus to the temple in accordance with the rituals and tradition of their people. Mary came for the rite of purification which required the sacrifice of a lamb or, if the family could not afford a lamb, two turtledoves or young pigeons were offered. Jesus, as a first-born child, was being presented to be consecrated to God. Both these rituals were in keeping with Torah, the holy teachings that define what is required of the people of the covenant. These rituals help define what it means to be Jewish.

Luke is reminding us here that Jesus was Jewish. Luke reminds us that the life of Jesus was shaped and enriched from the very beginning by rituals and traditions that were part of the covenant of his people. He reminds us that Jesus grew up in a house where it was understood that they lived in a special relationship with God and with the people of God, a relationship that came with both blessings and obligations.

In addition to the rite of purification and the rite of dedication which Luke refers to here in passing, Luke also gives us a more specific example of another Jewish tradition, the tradition of blessing.

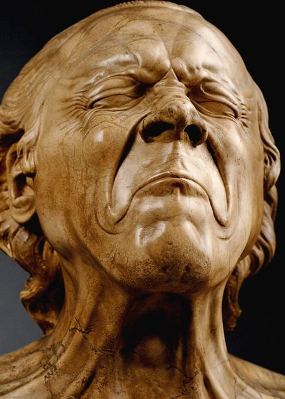

Luke tells us that about an old man named Simeon who was righteous and devout, and that the Holy Spirit had revealed to Simeon that he would not die until he had seen the Lord’s Messiah. When Simeon saw Jesus in the temple, he understood that God’s promise to him had been fulfilled. “Guided by the Spirit,” Simeon took the baby Jesus in his arms and praised God for keeping the promise.

The words Simeon spoke here have been part of my own formative tradition. We used to say them or sing them in the old King James language at the close of almost every worship service when I was growing up: “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: for mine eyes have seen thy salvation, which thou hast prepared before the face of all people; a light to lighten the Gentiles, and the glory of thy people Israel.”

When I was a boy those words sounded like magic. Listening to them, repeating them, I began to fall in love with the music and richness and power of language.

Simeon gave thanks to God that he had lived to see God’s salvation with his own eyes. And as he spoke his thanks, he also spoke words of blessing over the child.

As he gazed at the baby in his arms he had a vision of the child’s future. He said that the baby would become a light for revelation to the gentiles, that he would become the glory of Israel. He told Mary that her son was destined for the falling and the rising of many in Israel and that he would be a sign that would be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many would be revealed. Then, as he lifted his eyes from the face of the baby to the face of his mother, he saw something of her future, too.

Frederick Buechner captured this moment in all its tenderness and heartbreak: “What he saw in her face was a long way off, but it was there so plainly he couldn’t pretend. ‘A sword will pierce through your soul, he said.

“He would rather have bitten off his tongue than said it, but in that holy place he felt he had no choice. Then he handed her back the baby and departed in something less than the perfect peace he’d dreamed of all the long years of his waiting.”

Simeon wasn’t the only person to speak a blessing over Jesus that day. Anna, an aged widow who was also a prophet was also in the temple and when she saw the baby Jesus, “she began to praise God and to speak about the child to all who were looking for the redemption of Jerusalem.”

Anna and Simeon spoke words of blessing over the baby Jesus. They looked into the future on his behalf and spoke what they saw for him. With their words they set a course for him, or at the very least described their hopes for him.

We seem to have lost the tradition of blessing. We still have the word, but we seldom have the words. We say “God bless you” or even just “bless you” as if that was the whole thing when it is barely the beginning of a real blessing. We have lost the art of speaking goodness to and for each other, of using our words to call up goodness and identity and destiny into the present moment and project them into future.

I wonder what might happen if we began this new year with a blessing. What kind of healing and wholeness might we bring to the world if we learned to speak our hopes for each other and acknowledge the gifts we see in each other?

I invite you to try an experiment this New Year. I invite you to learn how to bless. I invite you to bless your children, your home, your loved ones and your friends. I invite you to speak goodness into the world.

So… I’ll go first. Receive a blessing, a benediction:

As this old year ends, your pains and frustrations will be transformed into wisdom. You will see a way forward with unfinished business. Fear and anxiety will have no hold on you. Throughout this new year, you will walk in the path of peace and joy. By your calm presence, you will be a blessing to all around you, and especially to those who are troubled in mind, heart or spirit. You will shine with the love of Christ and carry with you the peace of God which passes all understanding. You will walk in the Way of Jesus and speak goodness into the world in his name.

Amen.