John 17:6-19

It’s Mother’s Day today, so naturally, I’ve been thinking about my mom. I bought my mom a mug that said, “Happy Mother’s Day from the World’s Worst Son.” I forgot to give it to her.

I’ll never forget one Mother’s Day—we had a big family meal at Mom and Dad’s house but right after dinner Mom kind of disappeared. I found her in the kitchen getting ready to wash a sink full of dirty dishes. I said, “Mom, it’s Mother’s Day! Go sit down and relax. You can do the dishes tomorrow.”

My mom told me once that I’d never amount to much because I procrastinate too much. I said, “Oh yeah? Well just you wait.”

Mother’s Day was first proposed by feminist activists after the Civil War. They originally envisioned it as a day of peace to honor and support mothers who had lost sons and husbands to the carnage of the war.

In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation officially designating the second Sunday in May as Mothers Day.

And here’s an odd but important note: originally there was no apostrophe in Mother’s Day. Julia Howe and Anna Jarvis envisioned it as a day to honor allmothers. Plural. But the greeting card industry, the florists, and the candy makers quickly figured out a way to monetize the holiday. They individualized it and idealized it, and began promoting it as a day for you to honor your mother. In their advertising, Mothers Day (plural/all mothers) quickly became Mother’s Day with an apostrophe, as in your mother’s day (singular/possessive). Needless to say, the idea of it being a day to promote international peace pretty much vanished with the arrival of that apostrophe.

Mother’s Day became so commercialized that in 1943, Ann Jarvis, one of the women who had lobbied long and hard to make it a national holiday, tried to organize a petition to rescind Mother’s Day, but her efforts went nowhere. Frustrated, and literally at her wits’ end, Anna Jarvis died in 1948 in a sanitarium. Her medical bills, ironically, were paid by a consortium of people in the floral and greeting card industries.

Mother’s Day is one of those holidays that can be a great joy for some and a cringe-worthy day for others. In her annual Mother’s Day column Anne Lamott wrote: “This is for those of you who may feel a kind of sheet metal loneliness on Sunday, who had an awful mother, or a mother who recently died, or wanted to be a mother but didn’t get to have kids, or had kids who ended up breaking your hearts…” Lamott went on to acknowledge many of the ways that this Greeting Card holiday can be painful for many women…and also for many children.

Most pastors I know are ambivalent at best when it comes to Mother’s Day. It’s something of a minefield for us. We don’t dare let it go unmentioned, but at the same time we are very aware of those in our congregations who for one reason or another will be feeling that “sheet metal loneliness” that Anne Lamott described.

I said at the beginning of all this that I have been thinking about my mom. One of the great gifts she gave me was that she taught me to pray. She insisted that we give thanks before our meals and she sat next to me and listened as I prayed at bedtime. Sometimes she would pray with me. She also taught me that I could pray anytime and anywhere because God is always with me and always listening.

I was thinking of her as I read through the so-called High Priestly Prayer that Jesus prayed for his disciples in John 17, and it occurred to me that Jesus is “mothering” his disciples in this prayer as he prays for their safety and protection.

I’ve been blessed to know many people who are disciplined, devoted and powerful in their prayer life. I’ve also known quite a few who find prayer daunting and mystifying.

Robert McAfee Brown said that prayer, for many, is like a foreign land. “When we go there, we go as tourists. Like most tourists, we feel uncomfortable and out of place. Like most tourists, we therefore move on before too long and go somewhere else.”

If you’ve ever felt even a little bit uncomfortable or awkward about praying, if you’ve ever felt like a “tourist in a foreign land” when you pray, you might be able to find some comfort in the prayer Jesus prays here in the 17th chapter of John.

Jesus is clearly praying from the heart here. He knows the end is near. There is a lot to say and not much time left to say it. He prays for protection for these friends who have been his travel companions and students for three years and are heading into more difficulty than they can begin to imagine. He prays for their unity. That has to be comforting for them, and there is comfort here for us, too, because his request for protection and unity for his followers travels down through the ages to include us here and now. But there is something else in this prayer that might make us more at ease in our own prayers.

Jesus rambles. I mean no disrespect or sacrilege when I say that. In this prayer, Jesus rambles. We could, of course, ascribe that rambling to the writer of the Gospel. But we can’t deny it. In this wonderful, passionate, heartfelt prayer for the unity and protection of his disciples, Jesus rambles. A bit.

I, for one, find that very comforting. Because I ramble in my prayers. Often. I talk to God a lot, and it’s a rare blue day when I come into the conversation with all my thoughts completely organized. I suppose there are people who do, but that’s just not my personality type.

Over the years of my ministry I’ve been asked a number of times to teach a class or workshop on prayer. I confess it always catches me by surprise. Part of me wants to say, “How do you not know how to pray?” But I realized years ago that a lot of people think there is a proper method for praying and they suspect they’re not doing it right. Or they think that if they learn some secret formula for prayer they have a better chance of their prayers being answered the way they want them answered.

Here’s the thing. Prayer is not that complicated. There really aren’t any secrets.

Billy Graham said that prayer is simply a two-way conversation with God. And since God doesn’t talk all that much, that means that you can simply share your thoughts and feelings with God. That’s prayer. You don’t have to kneel or fold your hands—although if doing that helps you pray, then by all means do so.

If you’re the kind of person who likes more structure than that, you can try the ACTS model for prayer. A-C-T-S. A for Adoration, C for Confession, T for Thanksgiving, S-for Supplication.

Start by telling God all the wonderful things you’re seeing and experiencing and how much you love God for filling the world with such goodness. When’s the last time you said, “I love you” to God? You might be surprised at how much that simple act can change you.

So, Adoration. Then Confession. Take a moment for a little introspection and Confess your mistakes and shortcomings. You don’t have to beat yourself up. Don’t dwell on them, just acknowledge them. And remember: God is in the forgiveness business.

Follow that by Thanking God for all that’s good in your life, all the ways you’ve been protected and cared for, for the food on your table, for, well, everything that makes your life livable. Meister Eckhart said, “If the only prayer you ever say in your life is thank you, that will be enough.”

After you’ve said “thank you,” then you can ask for things. That’s the time for Supplication. Unless it’s an emergency, of course. If someone or something is bleeding or broken—and that includes your heart—you can lead with Supplication.

Adoration, Confession, Thanksgiving, Supplication. ACTS. The nice thing about this model is that it keeps you from hitting up God with your requests before you’ve even said a proper hello. It keeps us from treating God like Santa Claus or a celestial vending machine.

The point of prayer, after all, is not to get things from God or keep giving God your wish list. Remember, Jesus told us, “Your Father knows what you need before you ask.” (Matthew 6:8) The real point of prayer is to develop and deepen your relationship with God. “Prayer,” said Theresa of Avila, “is nothing else than being on terms of friendship with God.” Henri Nouwen said, “Prayer is the most concrete way to make our home in God.” Richard Rohr suggested, “What if instead of prayer, we used the word communing? When you’re communing with someone, it isn’t long before you’re loving them.”

As for doing it right…there are as many ways to pray as there are people praying. “Those who sing pray twice,” said Martin Luther. So singing is an option. So is dancing. You can pray while walking. You can pray while exercising. Saint Ignatius said, “Bodily exercise, when it is well ordered, is also prayer and pleasing to our Lord.” So there you go! Pray while you’re at the gym!

Back before I lost most of my hearing I used to lose myself in improvising on my guitar and I would offer that time to God as a kind of prayer. Kelsey Grammer said, “Prayer is when you talk to God. Meditation is when you’re listening. Playing the piano allows you to do both at the same time.” I think most musicians have had that kind of experience. There are times in music when you experience a holy presence that goes beyond words. You can experience that even when you’re just listening if you really immerse yourself in the music.

“The Glory of God is the human being fully alive;” said Irenaeus, “the life of a human being is the vision of God.” So if you’re singing or you’re dancing or riffing on your bagpipes, let that flow to the perichoresis of the ever-dancing Holy Trinity as a communion of Adoration, Confession, Thanksgiving and Supplication. Let that activity speak for your heart and don’t worry about impressing God with churchy-sounding words and phrases. “In prayer,” said Gandhi, “it is better to have a heart without words than words without heart.” Or as Martin Luther put it, “The fewer the words, the better the prayer.” In fact, some of the best prayers you will ever pray will be when you sit in silence in the presence of God who speaks in silence.

And don’t worry about whether you should address God as Father, or Jesus, or Spirit, or Lord. It’s all one to the Three-in-One. When you speak to one of them you speak to all three. In my own prayer life, I have begun using the Jewish tradition of addressing God as HaShem, which means “the Name.” For me it’s a way to remain deeply personal with God and at the same time honor the holiness of God.

Prayer is a powerful way to center yourself in difficult times. Adolfo Perez Esquivel, the artist and sculptor who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1980 for organizing and leading the opposition to Argentina’s military dictatorship said, “For me it is essential to have the inner peace and serenity of prayer in order to listen to the silence of God, which speaks to us, in our personal life and the history of our times, of the power of love.” Such an extraordinary thing—to find through prayer the strength and resolve to love in the face of brutal opposition.

“Prayer,” said Myles Monroe, “is our invitation to God to intervene in the affairs of the world.” “Prayer is not an old woman’s idle amusement,” said Gandhi. “Properly understood and properly applied, it is the most potent instrument of action.” “To clasp the hands in prayer,” said Karl Barth, “is the beginning of an uprising against the disorder of the world.”

Prayer is a powerful tool for difficult times. We tend to turn to it automatically in times of crisis. But we shouldn’t wait for a crisis to turn to God. As I said earlier, the main purpose of prayer is to deepen and strengthen our relationship with God. “The moment you wake up each morning, all your wishes and hopes for the day rush at you like wild animals,” wrote C.S. Lewis. “And the first job each morning consists in shoving it all back; in listening to that other voice, taking that other point of view, letting that other, larger, stronger, quieter life come flowing in.”

That, in the end, is what prayer is all about: letting that other, larger, stronger, quieter life come flowing in. And letting our lives flow more deeply into the life of God in whom we live, and move, and have our being.

And that brings us back around to the original intent for Mothers Day. It was intended to be something to strengthen the community and bring peace to the world. This Mothers Day, I invite you, through your prayers, to do just that.

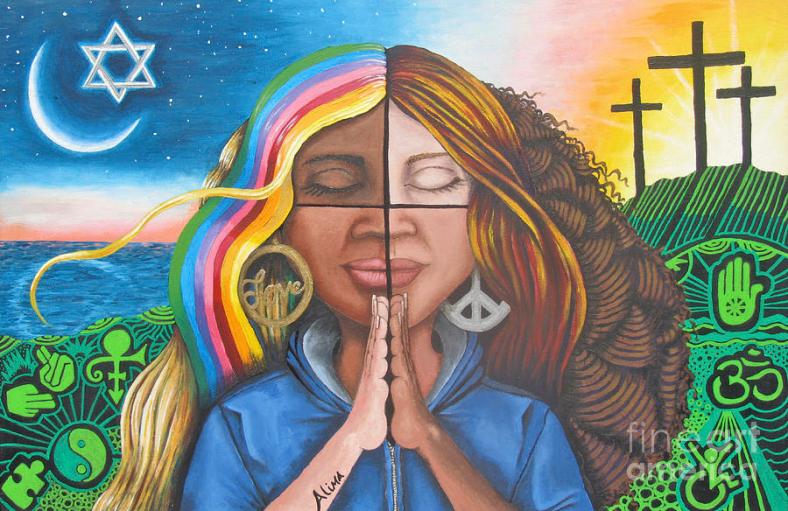

*Image © Alima Newton