John 14:8-17, 25-27; Acts 2

“When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place. And suddenly from heaven there came a sound like the rush of a violent wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. Divided tongues, as of fire, appeared among them, and a tongue rested on each of them. All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other languages, as the Spirit gave them ability.”

It’s no surprise that this is the text that usually gets all our attention on Pentecost Sunday. It’s a big, dramatic story. The language is intense and the narrative is filled with almost cinematic details that light up our imaginations! Violent wind! Tongues of fire! Everyone streaming out into the street speaking different languages! This outpouring of the Holy Spirit in the second chapter of Acts is so vivid and powerful, so action-packed and full of good stuff for motivating the church that it’s no wonder we return to it every year to be inspired by it and to have our own personal zeal and dedication rekindled.

This Pentecost story in the second chapter of Acts is an important part of our heritage; many call it the birthday of the church, but Diana Butler Bass reminds us that it’s really the birth of something much bigger. “It’s the birth of a new humanity, a new creation!” On the day of Pentecost, as the followers of Jesus proclaimed the Good News in the languages of everyone gathered there, Peter reminded the crowd of what the prophet Joel had said four or five hundred years earlier, “In the last days,” God declares, “I will pour out my Spirit upon all flesh.”

All flesh. All people. As St. Paul reminds us in Romans, “All who are led by the Spirit of God are children of God.”

The Pentecost story in Acts tells the story of that moment in history when the Spirit of God was poured out for all people, not just the insiders. In fact, the insiders quite literally rushed outside to bring the fire of God’s presence and love and Good News to everyone who would listen.

But there is another story in the New Testament about the outpouring of the Spirit, and over the past few years I have felt myself more and more drawn to that story from the end of the Gospel of John.

In chapter 20 of John, the disciples were huddled together in hiding. It was evening, three days after Jesus was crucified. The day had been an emotional roller coaster. Just before sunrise, Jesus’ tomb was found to be unsealed and empty. Mary Magdalen claimed that she had seen Jesus and spoken with him, but no one else had. And then suddenly, even though the doors were locked, there he was standing in the room with them! “Peace be with you,” he said. “As the Father has sent me, now I’m sending you.”

And then he breathed on them and said, “Receive the Holy Spirit.”

This is a much gentler and more subdued giving of the Spirit. It’s not as flashy as Luke’s Pentecost story, but it is very powerful in its own way. It’s more personal. More intimate. The Holy Spirit is given and received as the very breath of Jesus.

This is the culmination of a wonderful play on words that has been going on throughout John’s gospel since chapter 3 when Jesus told Nicodemus that “The wind blows wherever it chooses, and you hear its sound, but do not know where it is coming from or where it is going. So it is with everyone born of the Spirit.” In Greek, the language in which the Gospel of John was written, the word for wind and breath and spirit are all the same word. Pneuma. So when Jesus breathes on them in chapter 20 and says, “Receive the Holy Spirit,” it could also be understood as “receive the Holy Breath” or “Receive the Holy Wind.”

What does it do to our understanding of the Spirit if we can hear it all three ways: to hear it as the Spirit, the essence of God that resides with us and in us, guiding us and speaking to our spirits; but also to hear it as the very breath of Jesus filling our lungs, empowering our words when we speak; and then to also hear it as the wind of God that blows us where God wants or needs us to be? Receive the Holy Breath. Receive the Holy Wind. Receive the Holy Spirit.

I like the rambunctious giving of the Spirit in Acts 2. It’s a joyful and empowering picture of the Spirit at work. And it’s for everyone! All people! But as I said, I have been more and more drawn to the way the Gospel of John describes the movement and work of the Spirit. I find this quieter, gentler “Pentecost” more in keeping with my own experience and more consistent with the ways I have seen the Spirit move and work most often in others. I find that very often the work of the Spirit is so subtle that it’s not until I look back on the moment that I even realize that the Spirit was at work.

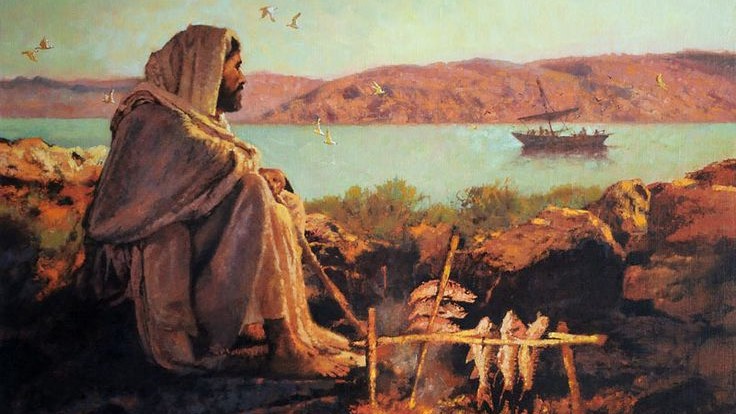

Let me give you an example. As I was preparing this sermon, I had done my research and gathered all the bits and pieces in my notes, and prayed, so that the only thing left to do was to start writing. And that’s where I was stuck. My brain needed more time to percolate all the things I had been reading and thinking. I guess I was still in sermon-avoidance mode. So I went online to Facebook just to get the synapses firing and blow out the cobwebs. As I scrolled through different posts, I came upon a painting of Jesus by Maria Brock. It is an arresting and well done painting, and there were two things I liked about it immediately. First, in this painting Jesus looks like a Palestinian. There’s an authenticity about it that makes it easy to say, “Yeah. Jesus could very well have looked like that.” But the thing that was really striking about this picture, at least for me, is that Jesus is smiling. He looks warm and friendly and understanding. And loving.

Staring at this marvelous picture of Jesus, I found myself thinking about our gospel text for today from John 14. This passage is part of the Last Supper Discourse, also called the Farewell Discourse. John describes Jesus gathered with his disciples on the night of his betrayal, taking advantage of their short remaining time together to prepare them for what is to come.

I have always imagined him being very somber throughout this whole discourse, after all, he’s sharing some very serious things with his disciples. But then I remembered that this dinner took place during the week of Passover, a joyful and celebratory time for the Jews. And looking at this picture where he’s smiling, where he looks so loving, I began to think, “What if this was his expression as he said all these difficult and necessary things? What if he was looking at them with deep love and gentleness and patient understanding?”

As I looked at that painting, I began to hear his words differently. The tone of voice changed and the words of Jesus came alive for me in a new way. I could hear Jesus saying with that gentle and loving smile, “Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not let them be afraid,” and those words went to my heart in a deeper way than ever before.

That, I believe, was a Holy Spirit moment. Finding that picture. Reimagining that scene of the text. Opening to the words of Christ in a new way. That’s the kind of thing the Holy Spirit does for us much more often, I think, than tongues of fire and speaking in unfamiliar languages.

It was a happy and festive season for their people, but it was probably not a happy and festive mood in the room where Jesus had gathered his disciples to give them the new commandment to love each other and to promise them the gift of the Spirit. They were anxious and afraid. They had so many unanswered questions. Jesus had told them that he would be departing from them and it had begun to sink in that soon they would be on their own. They needed some kind of reassurance.

In her commentary on the Working Preacher website, Meda Stamper said, “The promise of the Spirit does not come to completely faithful, courageous people, already loving one another and the world boldly, already worshiping in spirit and truth. It comes in the midst of confusion and fear, which has made them unable to grasp what he is saying, and it is the answer to that. Jesus makes the promise of the Spirit, emerging from the mutual love of the Father and Son for one another and for us, into which they and we are invited, at the very moment when such grace seems most beyond their grasp and ours.”[1]

Jesus tells them and us that simply in our love for one another we open our hearts to the Holy Spirit, the presence of God in us and with us, to guide us and make us bold enough love a world which, frankly, is not always loveable—a world that is sometimes threatening—but a world that is always and everywhere loved by God.

Jesus promises that when loving the world and each other feels like a trial, when it seems to be beyond our ability to find one more drop of grace and understanding in what Johannes Buetler called our “lawsuit with the world,”[2] when life, itself, feels like an ordeal, Jesus promises that we will have a Paraclete. An Advocate. The Spirit comes alongside us and abides in us in the same way that the Father abides in the Son and Jesus dwelled in the world. “When the physical presence of Jesus is no longer available, still the way, the truth, and the life are in us.”[3]

This is what the Spirit does. She comes into us like a breath and carries us forward like a powerful wind. She reminds us of all the things that Jesus has taught us. She gives us courage to witness, to convict or convince the world of the presence of Christ and the power of love. She gives us the energy and the courage to do in our time what Jesus did in his own time—to love each other and the world into health and wholeness.

“Jesus in John shows us what living love looks like in his own life of making God’s love for the world known,” said Meda Stamper. “He enacts love… in words and works: in dangerously truthful testimony to political and religious authorities; in a ministry of boundary-breaking healing and of feeding the physically and spiritually hungry; and in a life of humility,… friendship, and prayer. He tells us that we are to follow his example…”

Jesus enacts love and tells us to do the same. Jesus makes his own life an example of God’s love in the world and tells us to do the same.

This is the quieter Pentecost, the alternative Pentecost, a Pentecost centered in love. This is the Pentecost that empowers us to love God and to love our neighbors as ourselves. The Spirit is breathed into us, dwells in us, advocates for us, and flows through us as a witness to God’s love in a hurting world. Jesus calls us to live into the fullness of life in this Holy Spirit to bring light and love and restoration to all of creation.

Jesus breathes the Spirit into us to give us comfort and courage and peace. “Peace I leave with you,” he says. “My peace I give to you,” and the peace that Jesus gives us is the breath of the Spirit. It is the very presence of God in us. Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid. God is with you and in you.

Whether it’s with tongues of fire and a loud rush of wind, or with a whisper, a breath, or a breeze, may this Pentecost renew the power of the Spirit within you.

May the Spirit of God make you bold to love the world. May this Holy Spirit, the breath of Christ within you, empower you to be kind, to speak truth, and to stand for justice and fairness. May your life be centered in love. And may the peace of Christ, which passes all understanding, keep your hearts and minds in Christ Jesus.

[1] Meda Stamper, Commentary on John 14:8-17, 25-27

[2] Johannes Buetler, Paraclete, The New Interpreters Dictionary of the Bible

[3] Meda Stamper, Commentary on John 14:8-17, 25-27