Luke 16:19-31

One bright afternoon in heaven, three people showed up at the Pearly Gates at the same time. St. Peter called the first person over and said, “What did you do on earth?” “I was a doctor,” she said. “I treated people when they were sick and if they could not pay I would treat them for free.” “That’s wonderful, Doctor,” said St. Peter. “Welcome to heaven, and be sure to visit the science museum!” Then he called the second person over. “What did you do on earth?” he asked. “I was a school teacher,” the man replied. “I taught educationally challenged children.” “Oh, well done!” said St. Peter. “Go right in! And be sure to check out the buffet!” Then St. Peter called over the third person. “And what did you do on earth?” he asked. “I ran a large health insurance company,” said the man. “Hmmm,“ said St. Peter. “Well, you may go in but you can only stay for three days.”

Some people think that the parable of the rich man and Lazarus is about heaven and hell. And in a way, maybe it is, but not in the obvious way. Like all good parables, this story where the poor man is comforted after death and the rich man is left languishing alone in Hades is another one of those Jesus stories that should make us stop and rethink what we believe and what role that belief plays in our lives.

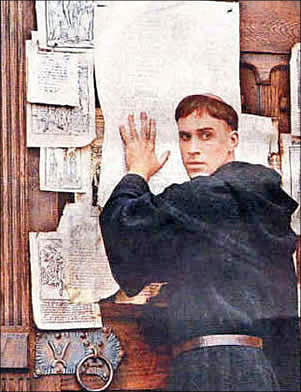

We Lutherans and many other Protestants are big on Grace. This was Martin Luther’s big breakthrough after all—the understanding that we don’t earn our salvation, but that God’s love and God’s grace is what saves us.

When I was in confirmation class many, many years ago, our whole class was required to memorize Ephesians 2:8-9: “For by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God— not the result of works, so that no one may boast.” The Lutheran curriculum we were following wanted to make it crystal clear that being saved was entirely dependent on God’s grace. For most of us at that age, being saved simply meant that you get to go to heaven when you die, and no one suggested that there might be other richer or more nuanced ways to understand it.

So Grace, we were taught, is your ticket to heaven and the only way in. The formula was pretty simple. You might do all the nice and good things it’s possible to do in the world, but that won’t get you into heaven because no matter how good and nice and helpful you are, you’re still going to sin. You can’t help it. It’s part of human nature. And sinful people can’t go to heaven, because no sin is allowed there. But, if you believe in Jesus, then God will forgive all your sins! You get a free pass. You get Grace with a capital G.

The problem with our Protestant theology of Grace is that too many people stopped with that overly simple middle-school understanding. Too many people came to believe that all they have to do is accept Jesus into their hearts as their personal Lord and Savior, and that’s it. Done.

This truncated understanding can lead to what Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace,” a belief that what you do or don’t do doesn’t matter because God will forgive you for Christ’s sake simply because you say you believe. This is like setting off on a thousand mile hike and stopping after the first 20 yards. At best, “cheap grace” leads to a very shallow personal theology and a me-centered spirituality. At worst it lays a foundation for an “anything goes” way of life with no sense of accountability. People who believe in this kind of “cheap grace” can sometimes do atrocious things, or leave very necessary things undone, and still think of themselves as “saved.”

Many of us cling to the gift of grace promised in Ephesians 2:8-9, and rightfully so, but too many of us stopped reading too soon; we failed to read on through verse 10 where it says, “For we are what he has made us, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand to be our way of life.” (NRSV)

I particularly like the way the New Living Translation renders verse 10: “For we are God’s masterpiece. He has created us anew in Christ Jesus, so we can do the good things he planned for us long ago.”

We are saved—rescued, healed, made whole, restored—by grace through faith. But “through faith” doesn’t just mean that we intellectually accept the idea of grace. Real faith opens our eyes to God’s grace at work in our lives and the world around us. Real faith moves us to embody and to enact God’s grace. Real faith moves us to do the good things God planned for us long ago. If we don’t do those good things, then faith becomes nothing more than a security blanket of wishful thinking to wrap around ourselves on dark nights of doubt and fear. As the Book of James says, “we are shown to be right with God by what we do, not by faith alone… For just as the body without the spirit is dead, so faith without works is also dead.” (James 2:24-26)

One of the themes in Luke and Acts is the presence and work of the Holy Spirit, and yet Luke doesn’t let us “spiritualize” things that put us on the spot. The examples of the “work of the Spirit” in Luke and Acts, especially as that work plays out in the ministry of Jesus, are practical, concrete, and challenging. As much as we might want to spiritualize the story of the Rich Man and Lazarus, it’s tough to explain away its central message, especially in light of what Jesus has to say about wealth and poverty throughout the entire Gospel.

The Gospel of Luke emphasizes that the status of the rich and poor is reversed in the kingdom of God. In the opening chapter of Luke, Mary sings, “He has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; he has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty.” (1:46-55)

In the Sermon on the Plain, Jesus says, “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled,” and then “woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation. Woe to you who are full now, for you will be hungry.” (6:20-25)

Luke makes it clear that “the poor” receive special attention in the ministry of Jesus and in the kingdom he is announcing. When he stands up to preach in the synagogue in Nazareth, he reads from the scroll of Isaiah, “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor.” (4:18)

When John the Baptist is in prison and sends one of his disciples to ask Jesus if he really is the one they’ve been waiting for, Jesus says, “Go and tell John what you have seen and heard: the blind receive their sight, the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised, the poor have good news brought to them.” (7:22)

When he is a dinner guest at the home of a Pharisee, Jesus tells his host and others, “Don’t invite all your friends to your banquets, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame and the blind.” (14:12) – because that’s who is invited to God’s banquet (14:21).

When the rich young ruler asks Jesus how he can inherit eternal life he is told to go sell all he has and give it to the poor. (18:18-30)

In Luke’s gospel Jesus makes it clear that having “treasures in heaven” is not just about piety; it is also about selling possessions and distributing wealth to the poor. (12:33; 18:22)

In Luke’s gospel, conversion doesn’t just mean accepting Jesus as your Lord and Savior or asking Jesus into your heart, whatever that means. When Zacchaeus the tax collector is befriended by Jesus, he gives half of his possessions to the poor and repays anyone he has defrauded four times over.

Concern for the poor is a central part of the ministry of Jesus, but it wasn’t invented by Jesus. Jesus himself stresses that it is the commandment of Torah. In Deuteronomy, Moses states: “If there is among you anyone in need, a member of your community in any of your towns within the land that the LORD your God is giving you, do not be hard-hearted or tight-fisted toward your needy neighbor. You should rather open your hand, willingly lending enough to meet the need, whatever it may be. Be careful that you do not entertain a mean thought, thinking, “The seventh year, the year of remission, is near,” and therefore view your needy neighbor with hostility and give nothing; your neighbor might cry to the LORD against you, and you would incur guilt. Give liberally and be ungrudging when you do so, for on this account the LORD your God will bless you in all your work and in all that you undertake. Since there will never cease to be some in need on the earth, I therefore command you, ‘Open your hand to the poor and needy neighbor in your land.’” (Deut. 15:7-11)

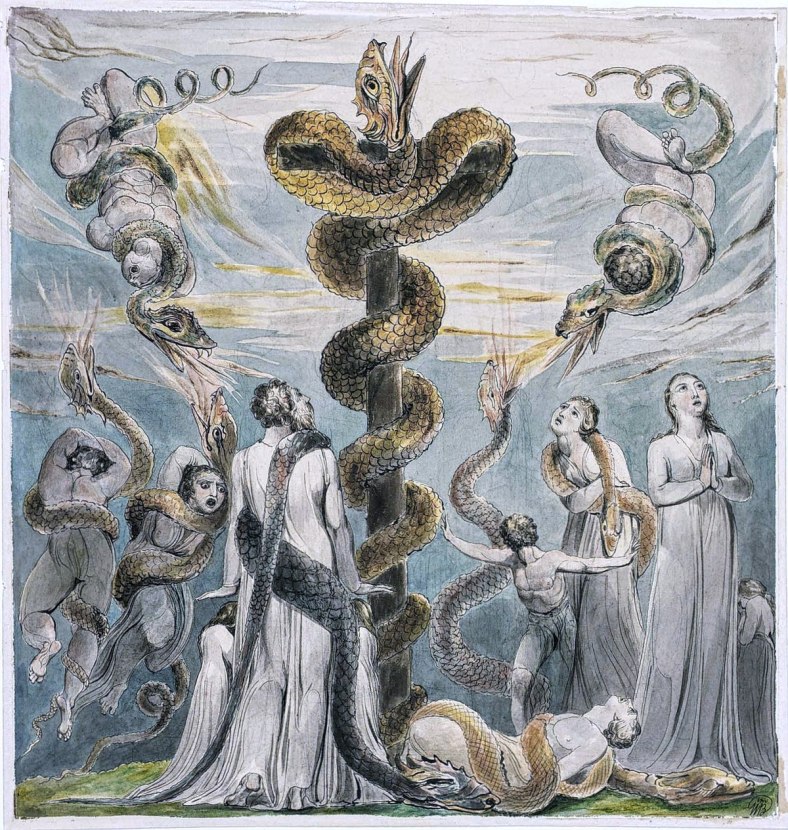

This parable of the rich man and Lazarus raises important questions. We’re not told that Lazarus did anything particularly noble or good. He was just poor. So why is he carried away by angels to be nestled and comforted in the bosom of Abraham after he dies? We’re not told that the rich man did anything particularly horrible, he’s just self-centered. So why is he in anguish in the flames of Hades after he dies?

Lazarus benefits from the default of grace. He is a descendent of Abraham, so he is included in God’s covenant with Abraham. He hasn’t done anything to remove himself from the covenant so he will spend eternity “in the bosom of Abraham,” enjoying companionship with others who have kept the covenant.

The rich man, on the other hand, removed himself from the covenant when he failed to “open his hand” to the poor and needy neighbor on his doorstep. He failed to even see Lazarus, much less see their kinship in the covenant of Abraham and the covenant of humanity. Instead of using his resources to help Lazarus, he used them exclusively to feed his own appetites. He is condemned to live forever in the burning loneliness that he, himself, created. By focusing only on himself during his life, he created a great uncrossable chasm which now separates him forever from the companionship of eternity.

“Some people, we learn, will never change,” says Amy-Jill Levine. “They condemn themselves to damnation even as their actions condemn others to poverty. If they think that they can survive on family connections—to Abraham, to their brothers—they are wrong. If they think their power will last past their death, they are wrong again.”[1]

There is a sad “too-little-too-late” moment at the end of this short story by Jesus. The rich man, realizing that there is no reprieve for him, asks Abraham to send Lazarus to warn his five brothers so they don’t end up “in this place of torment.” Abraham reminds him that Moses and the prophets have already warned them, and the rich man replies, “No, Father Abraham! But if someone is sent to them from the dead, then they will repent!” Abraham says simply, “If they won’t listen to Moses and the prophets, they won’t be persuaded even if someone rises from the dead.”

“We are those five siblings of the rich man,” wrote Barbara Rossing. “We who are still alive have been warned about our urgent situation… We have Moses and the prophets; we have the scriptures; we have the manna lessons of God’s economy, about God’s care for the poor and hungry. We even have someone who has risen from the dead. The question is: Will we—the five sisters and brothers—see? Will we heed the warning before it’s too late?”[2]

[1] Short Stories by Jesus, p. 271, Amy-Jill Levine

[2] Working Preacher.org; Barbara Rossing, Commentary on Luke 16:19-31, September 25, 2016