John 21:1-19

The Gospel of John comes to a very satisfying conclusion at the end of Chapter 20. In that chapter, the resurrected Jesus encounters Mary Magdalene by the empty tomb. In the evening of that same day he appears to the disciples who were huddling in fear in the upper room. Jesus greets them with a benediction of peace and breathes on them to bestow the Holy Spirit which will empower them for the work that lies ahead. A week after that, he appears to Thomas to address his doubts. The final words of chapter 20 feel like a conclusion: “Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples that are not written in this book. But these are written so that you may continue to believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.”

The end.

Except it’s not.

Just as you’re about to close the book, the narrator starts up again in chapter 21 saying, “After these things Jesus showed himself again to the disciples by the Sea of Tiberias, and he showed himself in this way.” And what comes next is a fishing story. Which is a little strange since fishing is not mentioned even once anywhere else in the entire Gospel of John.

The final chapter of John, chapter 21, is a bit odd in a number of ways. There is a general consensus among scholars that this chapter was added to the gospel at a later date, some say as much as 20 years after the original ending. Since John was the last of the gospels, most likely written sometime around 90 CE depending on who you ask, that would mean that this epilogue was written sometime around 110 CE or thereabout.

This epilogue, this fishing story, is not a story meant to inspire evangelism, although it has often been preached that way. It’s not a story meant to affirm and reinforce the bodily resurrection of Jesus, although it has often been preached that way, too. This is a story about civil disobedience.

So what was going on in the world and in the communities of Jesus people around that time that made it feel necessary to add this chapter? And why does this chapter take them so suddenly back to Galilee? And why are they going fishing?

To answer these questions, we need to revisit a little bit of history.

Jesus began his ministry in Galilee and that’s where he called his first disciples. The writer of John seems to assume that we already know that Peter and Andrew and James and John were fishermen who fished in the Sea of Galilee before meeting Jesus. John assumes we already know the story of how they dropped their nets and left their boats when Jesus walked by and said, “Follow me and I will teach you to fish for people.” But if we didn’t know those stories from Matthew, Mark and Luke, we would not learn them from John because John’s gospel hasn’t been at all interested in fishing. Until now. In the epilogue.

Fishing was an important industry in the empire and it was heavily controlled.[1] By law, the emperor owned every body of water in the empire and all the fish in those waters. Every last one of them. It was illegal to fish without a license and those licenses were expensive. Most fishing was done by family cooperatives who pooled their money to buy the license and the boats and nets. You could make a living but you wouldn’t get rich because about 40% of the catch went for taxes and fees. And you were probably making payments on the boat, too. After the fish were caught they would be carted or carried by boat to a processing center where the fish would be salted and dried or pickled, except for the large fish. I’ll come back to the large fish in a moment.

The most important processing center on the Sea of Galilee was just down the road from Capernaum in the town of Tarichaea. The Hebrew name for that town was Magdala Nunayya, which means Tower of Fish. Just a side note here: Magdalameans tower, so Mary Magdalene means Mary the Tower, which tells us something about her status among the apostles. Herod Antipas wanted to curry favor with the emperor Tiberias, so in the year 18 CE he established a city three and a half miles away from Tarichaea which he named Tiberias in honor of the emperor.

Herod built piers and fish processing facilities then invited people from all over the empire to come live in Tiberias and work in its fishing industry. Gentile pagans flocked to the town looking for employment on the Sea of Galilee which these newcomers now called the Sea of Tiberias. Almost overnight the Jewish family coop fishing businesses that had sustained people like Peter and Andrew and James and John found themselves in stiff competition with state-sponsored foreign fishermen from all over the empire, and the wealthy fish-processing town of Tarichaea/Magdala Nunayya began rapidly losing money to Herod’s processing plants in the city of Tiberias.

One of the consequences of all this was that opposition to Roman occupation and Herod’s administrative oversight began to intensify in Galilee, and Tarichaea became a hotbed of resistance. Eventually, that resistance became a revolt and a full-blown war.

In the year 70, the Roman general Titus completely leveled Tarichaea. The Galilean fishing industry would have been completely destroyed, but the people of the city of Tiberias took an oath of loyalty to the emperor, so they were allowed to continue catching and processing fish in the Sea of Tiberias. That same year, Titus sacked Jerusalem and destroyed the temple but the resistance to Rome’s heavy-handed power never entirely melted away. The fishing community of Galilee continued to harbor a core of that resistance that core of the resistance movement.

All of this is in the background of Chapter 21, this epilogue to the Gospel of John. This chapter was written about 80 years after the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus and for most of those 80 years Rome had been at war with the Jews which meant they were also at war with the Christians because as far as Rome was concerned, the Christians were just another Jewish sect, a sect which the Roman Senate had declared to be an “illegal superstition.” That declaration opened the door for persecution of Christians under Nero and Domitian and later emperors.

So back to the original question: what was going on in the world and in the communities of Jesus people around that time that made it feel necessary to add this chapter? In the year 112, Pliny the Younger who was serving as governor of Bithynia and Pontus wrote to Trajan, the emperor, and asked, “I have some people who have been accused of being Christians. What do you want me to do with them?” Trajan wrote back and said, “Well, don’t go hunting for them, but if someone is accused of being a Christian, just ask them to renounce their faith, take an oath of loyalty to the Emperor, and offer sacrifices to the gods of Rome. If they do that, let them go. If not, execute them.”

This was not an easy time to be devoted to Jesus—not that it had ever been easy. But now, if a neighbor publicly accused you of being a Christian you had a very hard choice to make. On top of that, the seemingly endless war that Rome was waging on Jews who showed the least bit of activism kept popping up in hot spots, and as far as Rome was concerned Christians were just another kind of Jews, which, to be fair, was often true since many Christians were Jews who followed Jesus. On top of all that, these early Jesus people had expected Christ to return at any minute to overthrow the Empire of Rome and replace it with the kingdom of God, but that had not happened yet. The original Apostles were all gone to their reward and the People of the Way were losing hope and direction. What do we do? How do we continue? How do we live in the life-giving Way of Jesus in the face of an oppressive and dehumanizing Empire?

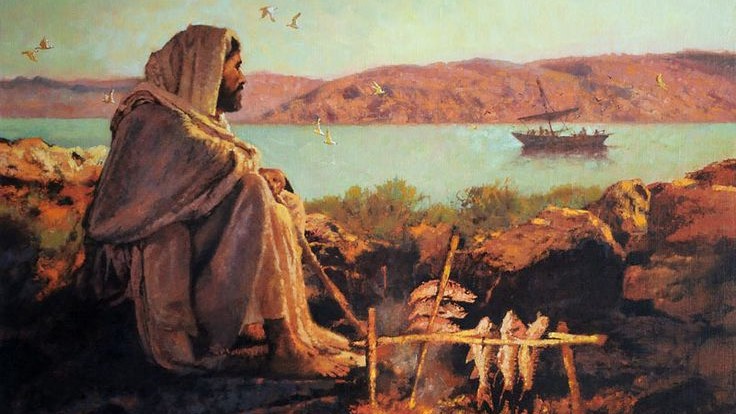

Chapter 21 acknowledges the presence of the empire right away. After these things Jesus showed himself again to the disciples by the Sea of Tiberias. Only the Gospel of John refers to the Sea of Galilee as the Sea of Tiberias. That name is used nowhere else in the New Testament. That’s the empire’s name for this body of water. It’s a reminder that the Emperor claims ownership of this sea which plays such a large role in the story of our faith. The emperor is in the story. But the writer of this chapter is telling us right from the top that even where the empire claims sovereignty, Jesus shows up to challenge that claim with a quiet but firm counter claim.

“Gathered there together were Simon Peter, Thomas called the Twin, Nathanael of Cana in Galilee, the sons of Zebedee, and two others of his disciples. Simon Peter said to them, “I am going fishing.” They said to him, “We will go with you.” This naming of the disciples is a roll call of the companions of Jesus who established Christ-following communities throughout the empire. This is a reminder to all those followers of Jesus and his apostles that we are all in the same boat even if the empire claims to own the sea.

So they go fishing all night. But they don’t catch anything. Frustrating. Disheartening. And doesn’t life in the church feel just like that sometimes. You do everything you know how to do and you get bupkis.

And that’s when they spot Jesus standing on the beach, waiting for them. They don’t recognize him right away. People usually don’t recognize the risen Christ right away. The disciples don’t recognize him until they follow his instructions, drop their net on the right side of the boat and then haul in so many fish that they can’t even lift the net into the boat. That’s when they recognize him.

When they got to the beach they found Jesus cooking some fish and bread over a charcoal fire and he invited them to breakfast. It’s easy to go right past that, but it’s important not to miss it. Jesus is already cooking a fish. Jesus already has one of the emperor’s fish. Jesus is engaged in an act of civil disobedience. And he’s about to make it an even bigger act of civil disobedience. “Bring some of the fish that you have just caught,” he tells them. So Simon Peter hauled the net ashore and found it was full of large fish. A hundred fifty-three large fish.

A hundred fifty-three fish is impressive. But the thing that would have been really impressive to the first people who read or heard this story was that they were large fish. Regular fish were sent to the processor to be processed. Large fish, however, were wrapped and put on ice and shipped off for the tables of the wealthy and nobility and even for the emperor, himself. Large fish, the emperor’s large fish, were not for consumption by common fishermen on the beach. But Jesus has other ideas. “Bring me some of the fish you have caught and come have breakfast.”

Jesus is making a statement. The sea does not belong to the emperor. The sea belongs to God. The fish do not belong to the emperor. The fish belong to all God’s people. In God’s economy the first and biggest and best of the world’s abundance does not automatically go to the wealthy and powerful. In God’s economy the abundant provision of the earth is for everyone. Jesus appropriates the emperor’s fish, large fish fit for the emperor’s own table, and creates a feast for his disciples, for the people who did the hard work of fishing.

After a nice reunion breakfast of roasted fish and bread, Jesus turned to Simon Peter and said, “Simon son of John, do you love me more than these?” The word “these” makes Jesus’ question hauntingly ambiguous. Does he mean more than these friends of ours, these other disciples? Does he mean “these things?”—do you love me more than your boats and your nets and your life as a fisherman? What are “these”? Maybe it’s all of the above.

Jesus asks Peter this “do you love me” question three times, and in the Greek text there is an interesting play on words using two different words for love, agape and phileo. Jesus asks Peter if he loves him with an agape love, the decisional, self-sacrificing love that puts the needs of the beloved first. Peter responds with phileo,the deep bond of brotherly love and friendship. Both words mean love and scholars note that they were often used interchangeably, but they’re not exactly synonyms and subtle nuances in meaning can flavor a conversation the way subtle differences in spices can change the flavor of a stew. There is tension in this conversation between Peter and Jesus, and that tension is emphasized by the subtle differences in the words each one uses for love.

Jesus repeats the question a second time and Peter repeats his answer. But the third time, Jesus asks the question differently, using the word for love that Peter has been using: “Simon son of John, do you love me like a brother?” That stings. Peter feels hurt, and you can feel the heat when he says, “Lord, you know everything. You know that I love you.”

This tense dialogue with Peter, with its play between agape and phileo, echoes a moment from the final teaching Jesus shared with his disciples on the night he was betrayed. As he sat at the table relaying his parting thoughts he said, “This is my commandment, that you love one another (agape) as I have loved you. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends (philon). You are my friends if you do what I command you.” (John 15:12-14)

That was the same night when Peter denied Jesus three times. Now, Jesus asks Peter three times to affirm his love and friendship, and three times he commands Peter to lead and care for those who will follow in the Way of Christ. Feed my lambs. Shepherd my sheep. Feed my sheep. With these words, Jesus reinstates Peter as a disciple.

Jesus wasn’t just speaking to Peter. Jesus was speaking to all his followers in every age.

Do you love me? Feed my lambs. Shepherd my sheep. Take care of people. Do justice, love kindness and walk humbly with God. Help the helpless and stand with the hopeless. Protect the vulnerable. Feed the hungry. Protest injustice. Embrace diversity, equity and inclusion, even if it breaks the rules of empire.

Follow me. You are my friends if you do what I command you. The risen Jesus speaks these words to Peter as both a challenge and an invitation. That challenge and invitation extends to anyone willing to follow Christ and be a disciple of the Way. That challenge and invitation extends to you and to me. And sometimes the abundant life in Christ and the feast of love and joy requires a little civil disobedience.

[1] Hanson, K.C., The Galilean Fishing Economy and the Jesus Tradition; Biblical Theology Bulletin 27 (1997), 99-111.