Mark 4:26-34

With what can we compare the kingdom of God…

What do you think of when you hear or read that phrase: the kingdom of God? I think it’s hard for us to really grasp what Jesus was talking about when he talked about the kingdom of God not only because he described it in metaphors and parables, but because a kingdom, itself, is a thing entirely outside of our experience for almost all of us.

Most of us think of kingdoms in terms of either physical territory or fairy tales, but clearly Jesus is talking about something that transcends mere physical boundaries and is a lot more real than fairy tales. A kingdom can simply be a territory ruled over by a king or queen, but it can also mean a sphere of authority or rule, and that might be closer to what Jesus is getting at: the rule of God. The authority of God. But even that is something most of us can’t relate to too well because we have never lived under the authority of a monarch or a lord or a master, and those monarchies that are still active in our world are either almost entirely symbolic or wildly dysfunctional or utterly dictatorial. And I don’t think we want to attribute any of those qualities to God.

Also, words like authority and rule can have a coercive edge to them, and the kingdom, as Jesus describes it, seems to be much more about influence, persuasion and cooperation. It’s more organic. It’s something that grows in us and around us and among us.

I have often used the phrase “kin-dom of God” for that reason—to try to capture some of the cooperative, love-based nature of God’s sovereign rule as Jesus describes it in the beatitudes and parables. Diana Butler Bass has called it the Commonwealth of God’s justice and mercy, and I think that might be even more in the right direction. Maybe. But it’s also important to remember that the kingdom of God is not a democracy. God is sovereign. God’s rule is absolute. Fortunately for us, so is God’s love, and that love is the very fabric of this thing Jesus is trying to describe as “the kingdom of God.” The kin-dom of God. The Commonwealth of God’s kindness.

When Jesus told these parables, and thirty-some years later when Mark wrote them down, trouble was brewing in Galilee and Judah and pretty much throughout all of Palestine. Landowners were putting pressure on tenant farmers for rents they could barely pay. Scribes from the temple in Jerusalem were demanding a crushing and complex levy of tithes from those same farmers. Herod Antipas was demanding taxes from the landowners because Rome was demanding taxes from him. Unemployment was high. Bandits roamed the highways. Soldiers patrolled everywhere. Rome’s colonial government was heavy-handed and oppressive to the point of brutality. People wanted a heavenly anointed messiah to step in and fix things before they exploded—or maybe to light the fuse and set off the explosion that everyone felt was coming. It’s no wonder that the disciples kept asking Jesus, “Is this the time when you will bring in the kingdom?”

Jesus kept trying to tell them and all the crowds following him, “No, the kingdom of God is not like that. It’s not what you’re thinking. It won’t do any good to simply replace one coercive external system with another one even if the ruler is God!”

The change has to be internal. It has to be organic. Seeds have to be planted. Human hearts and minds have to be changed. It’s not about imposing a new kind of law and order. It’s about implanting a new kind of love and respect. That’s what will fix the world.

“The kingdom of God is as if someone would scatter seed on the ground, and would sleep and rise night and day, and the seed would sprout and grow, he does not know how.”

For generations we had a family farm in Kansas—my mother’s family farm—where we grew winter wheat. Winter wheat is planted in late September or early October, depending on the weather. Not long after it’s planted, it starts to sprout. Beautiful little shoots that look like blades of grass start to poke their heads up out of the soil. And then just as they’re getting started, the cold hits them. And it looks like it’s killed them. They slump back down to the dirt and go dormant, and they’ll just lie there all through the winter. The ground will freeze. Snow will drift and blanket over them. And there’s nothing you can do.

All winter long you go about your business. You sleep and rise night and day. And then you get up one spring morning and notice that the weather is a bit warmer, and the snow is patchy or mostly gone, and you look out the window to see that you suddenly have a field full of beautiful green wheat starting to rise up out of the ground. It’s an amazing thing to see, and if you have half a sense of wonder, you thank God for the natural everyday miracle of it and marvel at it for at least a moment before you get on with your chores.

The kingdom of God is like that, says Jesus. It is seeds scattered on the earth. Seeds of ideas and vison. And sometimes it looks like they’ve died. Or been crushed. Or been frozen out or buried. Or simply forgotten. But they are still there, just waiting for their moment.

The kingdom of God is seeds of ideas and vision and understanding. They are ideas about fairness and justice and cooperation. They are an understanding about fuller and more generous ways to love each other and take care of each other. The kingdom is a resolve to make a world that is healthier for everyone. It’s a resolution to embrace God’s vision for how the world is supposed to work—a world where everyone is housed and everyone is fed and everyone can learn and everyone is safe and everyone is free to be their true self. The kingdom is a determination to repair the damage we’ve done and restore creation so that we and all the creatures who share this world with us can breathe clean air and have clean water.

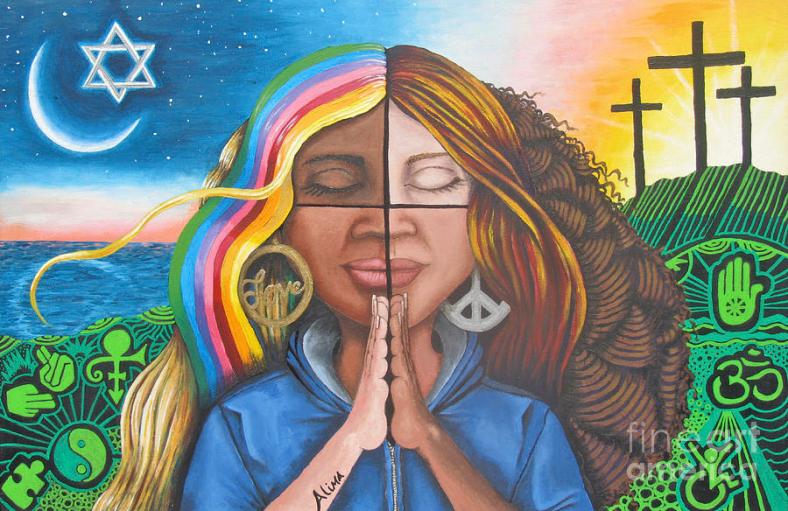

The kingdom of God, the rule of God, the reign of God, the kin-dom of God, the Commonwealth of God’s justice and mercy is a commitment to let justice roll down like water and to show each other kindness and to walk humbly with God and with each other. It is a continual correction of our vision so we keep learning how to see the image and likeness of God in each other—in each and every face we face so that racism and classism and every other kind of ism evaporate from the earth. It is the seed of courage taking root in our hearts and minds so that we learn not to be afraid of something or someone simply because it or they are different from us or from what we know or what we expect or what we are used to.

“With what can we compare the kingdom of God, or what parable will we use for it?,” said Jesus. “It is like a mustard seed, which, when sown upon the ground, is the smallest of all the seeds on earth; yet when it is sown it grows up and becomes the greatest of all shrubs, and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade.”

The mustard seed! That tiny seed that produces the most egalitarian, most democratic of plants! That’s what God’s kingdom is like. It freely and bounteously shares itself and all that it has. Given half a chance it spreads itself everywhere. The mustard plant doesn’t care if you are rich or poor. You don’t have to buy one. It will come to you and give you and your family food and medicine and spices for your cuisine and healing oils for what ails you. A most amazing, versatile and humble plant. And it starts as just a little tiny seed.

The kingdom of God is the planting of seeds. The seeds don’t have to be eloquent preaching or brilliant explanations of theology—probably better most of the time if they’re not. “Preach the gospel at all times,” said St. Francis. “When necessary, use words.” At a time when the city of Assisi was a rough and dangerous place, Francis would walk through the town from the top of the hill to the bottom and say as he went, “Good morning, good people!” When he got to the bottom of the hill he would turn to the brother who accompanied him and say, “There. I have preached my sermon.” What he meant was he planted a seed—he had reminded the people that the day was good and that they had it in themselves to be good people.

The seeds of the kingdom may be little acts of habit, like bowing your head for a moment to say grace before a meal in a restaurant, even if you don’t say it out loud. That simple thing might remind those around you to pause, to be thankful, to remember all the connections that bring food to our tables, to remember the goodness of the earth and the sweat of the farmers, to remember the presence of God.

The seeds of the kingdom might be small acts of kindness. When Oscar Wilde was being brought down to court for his trial, feeling more alone and abandoned than he had ever felt in his life, he looked up and saw an old acquaintance in the crowd. Wilde later wrote, “He performed an action so sweet and simple that it has remained with me ever since. He simply raised his hat to me and gave me the kindest smile that I have ever received as I passed by, handcuffed and with bowed head. Men have gone to heaven for smaller things than that. It was in this spirit, and with this mode of love, that the saints knelt down to wash the feet of the poor, or stooped to kiss the leper on the cheek. I have never said one single word to him about what he did … I store it in the treasure-house of my heart … That small bit of kindness brought me out of the bitterness of lonely exile into harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.”

The seeds of the kingdom might be a word of affirmation and encouragement when it’s needed most. Helen Mrsola was teaching ninth graders new math years ago. They were struggling with it. The atmosphere in the classroom was becoming more tense and irritable every day. So one Friday afternoon Helen decided to take a break from the lesson plan. She told her students to write down the name of each of their classmates on a piece of paper, then to also write down something nice about that student. She collected the papers, and over the weekend Helen compiled a list for each student of what the other students had written. On Monday, she gave each student a paper with list of what the other students liked about them. The atmosphere in the class changed instantly; her students were smiling again. Helen overheard one student whisper, “I never knew that I meant anything to anyone!”

Years later, a number of the students, all young adults now, found themselves together again at a school function. One of them came up to Helen and said, “I have something to show you.” He opened his wallet and carefully pulled out two worn pieces of notebook paper that had obviously been opened and folded and taped many times. It was the list of things his classmates liked about him. “I keep mine in my desk at work,” said another classmate. Another classmate pulled hers out of her purse, saying she carried it with her everywhere she went. Still another had placed his in his wedding album.

The kingdom of God. The rule of God. The reign of God. The kin-dom of God. The Commonwealth of God’s kindness. . .

To what shall we compare it?

It’s like seeds scattered on the earth, says Jesus. It’s like mustard seeds. Seeds of righteousness. Seeds of justice. Seeds of vision. Seeds of help. Seeds of hope. Seeds of mercy. Seeds of peace. Seeds of affirmation. Seeds of goodness. Seeds of kindness. Seeds of love.

You don’t know how they grow. But oh, they do grow.

On earth as in heaven.