Back in the bad old days, there was a dismal little mill town where just about everything was owned by two miserly old brothers who were not interested in much of anything except making money. They owned the mill where the people worked, they owned the houses the workers lived in, they owned the only store in town, in fact the only thing that the brothers did not own in that town was the church.

The pastor of the church was a good-hearted man, and it troubled him deeply to see the people of his parish struggling to survive on their meager wages, so he frequently sent letters to the two miserly old brothers asking them to use their wealth to improve the life of their workers, the people of the town.

Now it happened that one of the brothers died and the pastor was summoned to the brothers’ mansion to plan for the funeral. As he sat down across from the surviving brother, he noticed that the old penny-pincher had a pile of letters neatly stacked in front of him. The old man laid his hand on the stack of letters, looked the pastor in the eye and said, “Pastor, I’ll give the town everything you ever asked for in these letters if you’ll say in my brother’s eulogy that he was a saint.”

Now the pastor was a very truthful man, and he wasn’t sure how he would be able to do this, but the needs of the town were great and the old miser had offered him a way to meet those needs. So on the day of the funeral, the pastor stood up in the pulpit, prayed silently for a moment, then said, “The man in this casket was a miserly skinflint, a greedy, mean-spirited thief who cheated his workers out of what they were owed so he could line his own pockets. He was, all-in-all, a miserable excuse for a human being… But compared to his brother, he was a saint.”

On this All Saints Sunday, it seems appropriate to take a moment not just to remember the saints who have gone before us, but to think about what it is to be a saint.

A little girl went to church with her grandparents one Sunday in a huge, old, stone church with lots of beautiful stained glass windows. The little girl asked her grandmother, “Who are all those people in the windows? “Oh, those are saints,” said her grandmother. “There’s Saint Teresa, and Saint Mary, Saint Peter, Saint Paul, Saint John…” When she got home she told her mom and dad all about grandma and grandpa’s magnificent old church with the beautiful windows depicting all the saints. Her dad, curious about how much she understood, asked her, “What is a saint?” She thought for a minute then replied, “A saint is somebody the light shines through.”

I think that’s the best definition of a saint that I’ve ever heard: A saint is someone the light shines through.

Someone delving through the archives of the town of Milford, Connecticut discovered the minutes from a town meeting in 1640. Among the other items of town business, this was recorded for posterity: “Voted that the earth is the Lord’s and the fullness thereof; Voted that the earth is given to the Saints; Voted that we are the Saints.”

I’m not sure how the people of Milford understood it in 1640, but there is a lot of truth in what they were saying. We are the saints. Or at least we’re supposed to be. We are called to be the people the light shines through. That, at least, is how St. Paul used the term.

When he addressed his letter to the followers of Jesus in Rome he wrote, “To all who are in Rome, loved by God and called to be saints…” His letter to the Jesus followers in Corinth begins in a similar way: “To the church of God that is in Corinth, to those who are sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints…” His greeting to the Philippians is only slightly different: “To all the saints in Christ Jesus who are in Philippi, with the bishops and deacons: Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.”

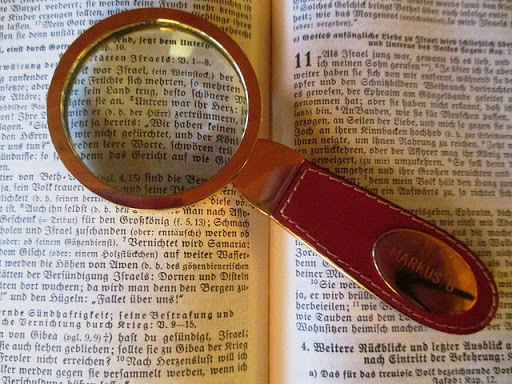

I really love the way Eugene Peterson translated the opening of 1 Corinthians in The Message Bible: “I send this letter to you in God’s church at Corinth, Christians cleaned up by Jesus and set apart for a God-filled life.”

It makes a lot of sense to me to think of saints as people who are being “cleaned up by Jesus and set apart for a God-filled life.”

The Greek word for “saints” is hagiois. It literally means “the holy ones” or “sacred ones,” persons who are consecrated and dedicated to serving God. In the early church, saints weren’t just people who were particularly pious or “saintly” or canonized by the church. The saints included all the followers of Jesus, everyone who was dedicated to living in the Way of Jesus in the beloved community. You don’t have to read very far in Paul’s letters to the Corinthians to realize that those “saints” were still very much in the process of being “cleaned up by Jesus. ” But Paul still regarded them as saints—a people set apart to show the world what the kin-dom of God, the commonwealth of God’s justice and kindness, could look like.

Saints are people who are awake to, or at least awakening to the love of God, so they try to live a “Christian” life—a life characterized by its integrity with the teaching of Jesus, a life glowing with the love that flows from Christ, a life of compassion consistent with the compassion of Jesus—in short, saints are people who are trying to live a life of deep relationship with Jesus. And with each other.

“The Christian life,” wrote Marcus Borg, “is about a relationship with God that transforms us into more compassionate beings. The God of love and justice is the God of relationship and transformation. . . . The Christian life is not about believing or doing what we need to believe or do so that we can be saved. Rather, it’s about seeing what is already true — that God loves us already — and then beginning to live in this relationship. It is about becoming conscious of and intentional about a deepening relationship with God.

“The Christian life is not about pleasing God the finger-shaker and judge,” he continued. “It is not about believing now or being good now for the sake of heaven later. It is about entering a relationship in the present that begins to change everything now. Spirituality is about this process: the opening of the heart to the God who is already here.”[1]

Saints are people who are learning to open their hearts.

Saints are people who understand that life and love are bigger than what we see. It’s tempting to think of the company of saints, the communion of saints as our own little church, especially if we spend a lot of our time and energy focused on the life of our congregation with all its joys and challenges. But it’s also important to remember that the Church of Jesus Christ, the Community of Faith, the Company of Saints is bigger than we can see. It’s important to remember that it has outposts in surprising places and manifests itself in surprising ways, that it stretches across time and space in ways that go far beyond our doors, beyond our local streets, beyond our county, state and nation. It goes beyond our time and connects us to all the saints who have gone before us and all who will come after.

The Letter to the Hebrews reminds us that we are surrounded by a great Cloud of Witnesses. We profess in the creed that we believe in the Communion of Saints. In a way that transcends both our vision and our understanding, those who have gone before us gather with us around the bread and the cup.

Stop and think for a moment of those who surround you this morning… the people who are present with you today in your heart and mind, who are present in faith…

In The Sacred Journey, Frederick Buechner wrote:

“How they do live on… and how well they manage to take even death in their stride because although death can put an end to them right enough, it can never put an end to our relationship with them. Wherever or however else they may have come to life since, it is beyond a doubt that they live still in us.

“ Who knows what ‘the communion of saints’ means, but surely it means more than just that we are all of us haunted by ghosts because they are not ghosts, these people we once knew, not just echoes of voices that have years since ceased to speak, but saints in the sense that through them something of the power and richness of life itself not only touched us once long ago, but continues to touch us.

In my last year of seminary, I had a profound mystical experience of the Communion of Saints. I was attending Easter morning worship at a little Lutheran Church in Oakland that had been rebuilt in 1907 after the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906. As I sat waiting for the service to begin, I found myself thinking of all the generations of people who had been part of that community of faith over the years. I imagined them singing old, familiar hymns, clothed in their austere Sunday Best during the years of the Great Depression. I imagined soldiers and sailors in uniform during World War II. I imagined kids in bell-bottoms and beads during the ‘60s. In my imagination I could see them all, clothed in the style of their times, singing the Easter hymns decade after decade. As I looked around, I couldn’t help but notice all the older people who sat alone, and I was suddenly struck that each of them had someone beside them—someone invisible to the sight of the eyes, but not to the sight of their hearts. I had a powerful sense that the saints from all those eras were gathered around the altar and in the sparsely filled pews. When I got back to my seminary apartment, I wrote a poem while the experience was still fresh in my mind.

Easter in a Dying Church (1996)

They come because they have always come…

and on this day of days,

not to pass through the beckoning door,

not to let their careful footsteps drum

old echoes from the wooden floor

would deny the pattern of their ways

and all the times that they have come before.

They sit where they have always sat…

each in the customary pew,

with room enough for all,

even for the visiting few

who do not hear the sweet, unearthly voices

singing Alleluia in memories so loud;

room enough for those who do not recall

the passings, the accidents, the choices

which have thickened the witnessing cloud

and left this sparse, embodied remnant of the hosts

surrounded by their holy ghosts.

They come to meet where they have always met…

to taste the wine with a beloved friend

who has faded from sight

but still shares the cup in the world without end,

to break bread with the cherished spouse

who, though swallowed by the light,

still prays beside each member of this house,

to meet children, uncles, sisters, mothers,

cousins, aunts, fathers, brothers,

in soul or body distanced from their common place—

yet present in this sacred space.

They come to be seen with the unseen…

to testify to the most revered of their presumptions:

that before and beyond here and now

the empty tomb

leaves a hole in all assumptions.

May we all continue to be cleaned up by Jesus. May we all become people the light shines through until that day comes when we become completely transparent in the great cloud of witnesses.

May we be saints…for the sake of the kin-dom of God.

[1] The Heart of Christianity, Marcus Borg